Writing Sanskrit

Introduction: The script-agnostic nature of Sanskrit

Open any Sanskrit text and you'll find something unusual: it could be written in elegant Devanāgarī, angular Bengali, flowing Thai, geometric Tibetan—even read right to left or top to bottom. Why? Because Sanskrit doesn't belong to any one script, it belongs to all of them. Sanskrit started as an oral language and didn't have a writing system of its own for a really long time. You might say that all languages are oral and that's true but for most of Sanskrit's life it was never written down. Sure, writing came much later than spoken languages and that's true for all languages. But here's the difference: some languages got their own custom-made writing system.

Most languages have one writing system. English uses Latin letters. Arabic uses Arabic script. But Sanskrit is different. It has borrowed and adapted over 40 different writing systems throughout its history. Think about other ancient languages. Cuneiform was invented specifically for Sumerian. The earliest cuneiform tablets are primarily administrative records tracking livestock, grain, and other commodities. Over several centuries, it evolved from pictographic signs into a full writing system capable of expressing complete texts in Sumerian and later adapted for Akkadian, Hittite, and other languages. Egyptian Hieroglyphs were created for Egyptian. Chinese Oracle Bone script was developed for Chinese. These languages got custom built writing systems. So what makes Sanskrit different? Sanskrit, by contrast, was never given a purpose built script as it has always borrowed and adapted existing writing systems. It just borrowed whatever script was locally available. The primary script used to write Sanskrit is called Devanāgarī but was not invented for writing Sanskrit. During its lifecycle various scripts have been used to write Sanskrit. Some of the scripts used to write Sanskrit are:

- Balinese

- Bengali and Assamese

- Bhaikshuki

- Brāhmī

- Grantha

- Gujarati

- Gurmukhi

- Javanese

- Kaithi

- Kannada

- Kharoshthi

- Khmer

- Latin

- Malayalam

- Modi

- Mongolian Galik

- Nandinagari

- Newar

- Odia

- Phags-pa

- Rañjanā

- Saurashtra

- Śāradā

- Siddhaṃ

- Sinhala

- Soyombo

- Tai Tham

- Tamil (rare)

- Telugu

- Thai

- Tibetan

- Tigalari

- Tirhuta

- Turkestani (Tocharian, Khotanese, and other Central Asian Brāhmī scripts)

- Zanabazar Square

An important thing to note here is that a lot of the scripts above have evolved from Brāhmī script and many of these scripts are now obsolete.

Major Sanskrit scripts

- Indian scripts

- Namely Devanāgarī, Bengali, Assamese, Gujarati, Kannada, Oriya, Telugu, Malayalam were widely used by people in religious, ceremonial and scholarly works.

- Grantha

- Was the widely used script in Tamil region to write Sanskrit as writing in Tamil was not suitable. The modern Malayalam, Tigalari, Sinhala, Thai, Javanese, etc. are derived from this script.

- Sharada

- Was the principle literary script used in Kashmir to write Sanskrit. The modern Gurumukhi script is derived from this script.

- Ranjana

- Is a beautiful calligraphic script primarily used in Nepal. A variation of this script called Lantsha, Wartu is used in Tibet and parts of China.

- Newar

- Also known as Nepali script is used to write Nepal Bhasha (language) and Sanskrit. It is quite similar to Bengali and Devanāgarī.

- Tirhuta

- Also known as Maithili was used in Bihar and Nepal to write Maithili language and Sanskrit.

- Tigalari

- Is used in coastal region of Karnataka which is a derivative of Grantha.

- Sinhala

- Is used to write Sinhala and Sanskrit in Sri Lanka. Many Buddhist works are written in this script.

- Nandinagari

- Was mainly used in Karnataka to write only Sanskrit which is derived from Nagari the precursor to Devanāgarī.

- Siddham

- Is a Buddhist script developed in North India but currently used in Japan, China and Korea to only write Sanskrit. It is a highly calligraphic and aesthetic script.

- Bhaikshuki

- Was used around the 11th and 12th centuries CE in eastern parts of India and parts of Tibet and Nepal.

- Kharoshthi

- Is an ancient script written from right to left and was used to write Sanskrit and Gandhari. It was in use from the middle of 3rd century BC until it died in its homeland around the 3rd century CE in present day Afghanistan and Pakistan.

- Tamil and Gurumukhi (Punjabi)

- Do not contain complete repertoire of Sanskrit letters and hence are rarely used for Sanskrit and even if they are used to write it they are modified.

- Tibetan

- A Buddhist script derived from Brāhmī used in Vajrayana Buddhism is used to write religious Sanskrit works in Tibet, Nepal, and Mongolia.

- Phags-Pa

- Is a script written vertically and is derived from Tibetan used in Mongolia and Tibet to write various languages including Sanskrit.

- Siddham

- Is a Buddhist script developed in North India but currently used in Japan, China and Korea to only write Sanskrit. It is a highly calligraphic and aesthetic script. When Buddhism spread to China, monks didn't adapt Chinese characters to write Sanskrit, they learned Siddham script instead. This shows Sanskrit's dependence on phonetic alphabets and hence Chinese script cannot be used to write Sanskrit. Why? Because Chinese is a logographic system where each character represents a word or concept, not individual sounds. Sanskrit, by contrast, requires precise phonetic notation: it has complex sound combinations, vowel length distinctions, and sandhi rules that alter sounds at word boundaries. Chinese characters simply couldn't capture this phonetic precision. For ritual accuracy in mantras and chants, monks needed a phonetic alphabet which is why they turned to Siddham, a Brahmic script, rather than adapting Chinese characters.

- Soyombo and Zanabazar Square

- Scripts are influenced by Tibetan and developed in Mongolia.

- Mongolian Galik

- Is non Brāhmī script used to write Sanskrit.

- Turkestani scripts

- Several historic scripts derived from Central Asian Brāhmī script are Tocharian, Khotanese, Tumshuqese and so called Uyghur Brāhmī are collectively known as Turkestani used to write Sanskrit.

- Latin script

- Sanskrit can now be also written in Latin script with modification named International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST).

Brāhmī Script History

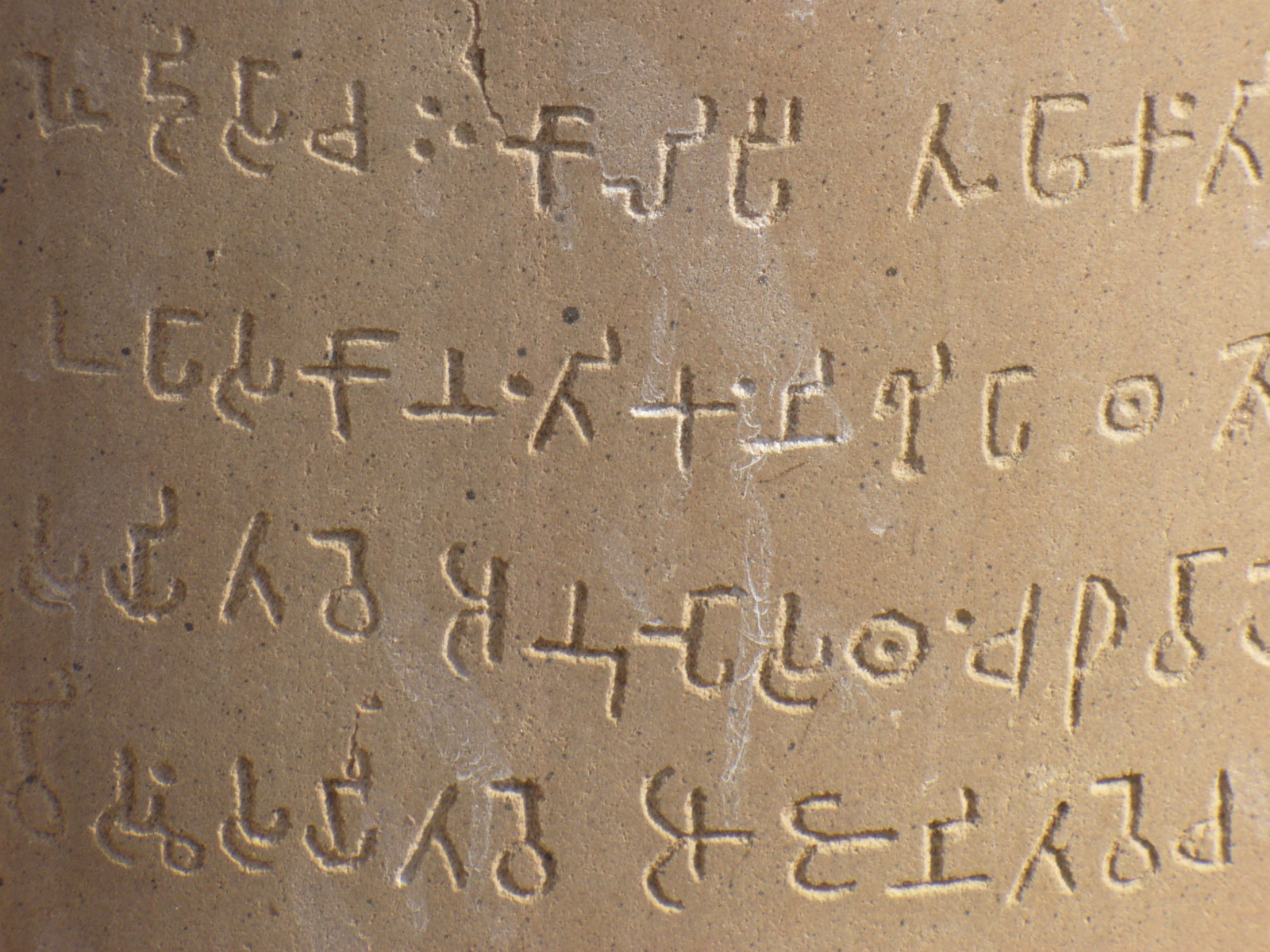

Sanskrit has been written in over 40 different scripts throughout its history! Sanskrit is script-agnostic. But most of those scripts are derivatives of the Brāhmī script. Brāhmī script is an ancient writing system ancestor to all Indian scripts except Kharoshthi. Its origin is uncertain and debatable as academics are still fighting over how the script was developed. It first appears as fully developed system in the 3rd century BCE found on inscriptions on rocks from emperor Ashoka's reign. The inscription on the original Sarnath pillar is known as the Schism Edict, warning against division within the Buddhist Sangha (monastic community). Translation:

"No one shall cause division in the order of monks. Whatever monk or nun causes division in the Sangha shall be made to wear white clothes [expelled] and to reside apart from the monastery. This is my command, and may it endure for as long as my sons and great-grandsons reign."

The Devanāgarī script used for writing Sanskrit and other Indian languages has evolved over a period of more than two thousand years. Following timeline has been documented showing the overall development of Brāhmī evolving into the Devanāgarī script.

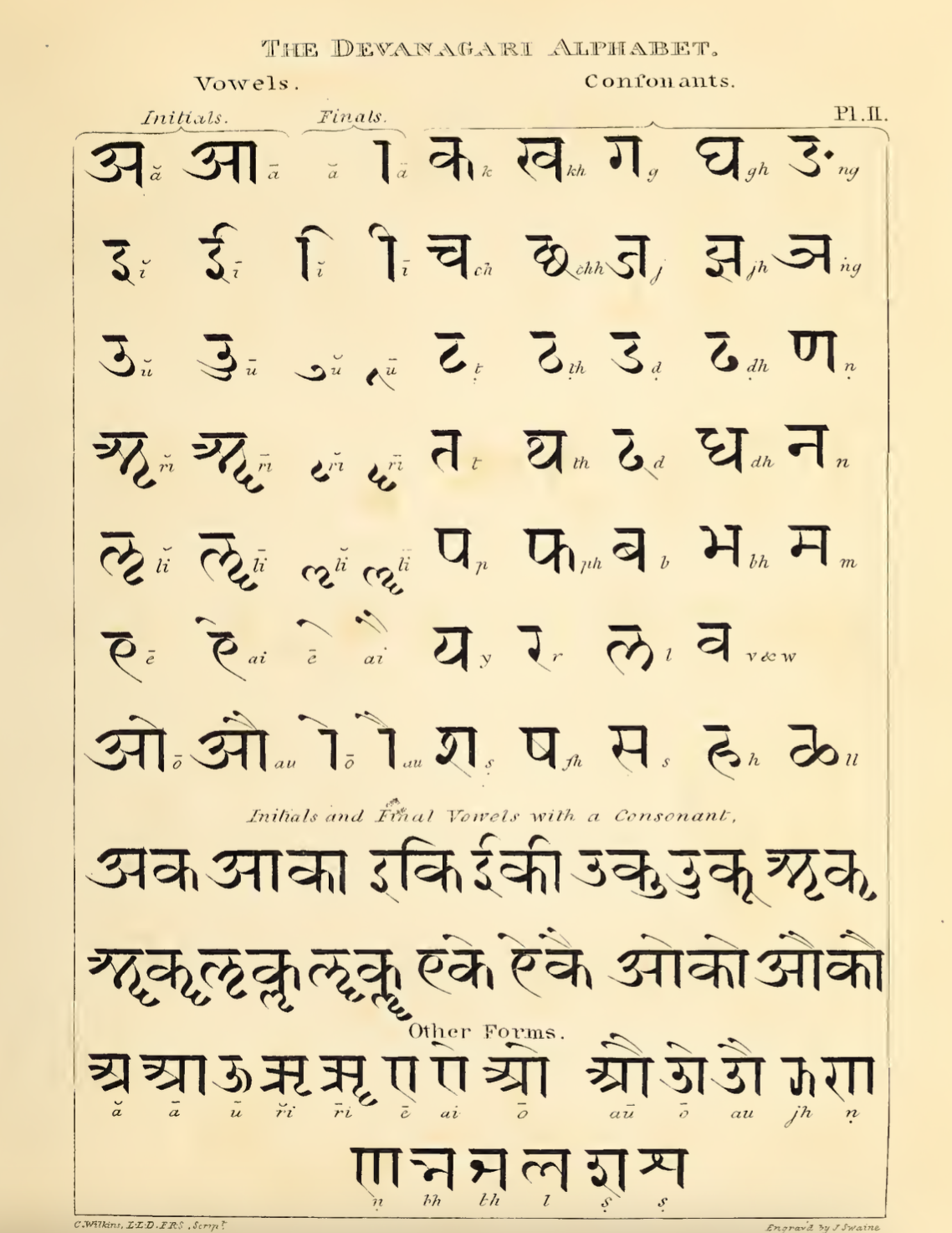

Devanāgarī: The Abugida script

The name Abugida comes from the Ethiopian Ge'ez script and is formed from the first four syllables 'ä, bu, gi, da similar to how we say a, b, c, d in English. Abugida is one of the three major phonetic writing system types. In an Alphabet (like Latin/English) vowels have equal status to consonants and have separate letters. The word "alphabet" comes from the first two Greek letters alpha and beta. In an Abjad (like Arabic or Hebrew) only consonants are written with vowels absent or marked optionally. In an Abugida like Brāhmī or Devanāgarī each basic symbol represents a consonant with an inherent vowel and in Sanskrit this vowel is "a" (अ).

Sanskrit now is primarily written in Devanāgarī which is an Abugida script. An Abugida is a writing system where each basic symbol represents a consonant with an inherent vowel and form a consonant-vowel unit. Each unit is based on a primary consonant and a secondary vowel. Vowels are indicated by modifying marks to the base consonant using something called as diacritic marks. This is how it works for Devanāgarī:

- Each letter = consonant + default vowel. In the case of Sanskrit the default vowel is "a".

- To write other vowels you add marks to the consonant. In Devanāgarī the sign for the vowel following a consonant is then added to right, to the left, above or below the consonant sign.

- To write just a consonant (no vowel) you use a special mark

Example: Base consonant क = "ka"

To write different vowels with क

- कि = add mark ि for ki

- की = add mark ी long "ī" kī

- कु = add mark ु for ku

- कू = add mark ू for long "ū" kū

There is no sign indicating the vowel: a. It is the most

frequent vowel in Sanskrit and seemed most economical to have its

presence assumed whenever no other other vowel was

explicitly present.

To write just क "k" with no vowel: क्

In Devanāgarī the mark ् to indicate the absence of a vowel is

called a Virāma a small diagonal stroke below the consonant sign.

This works well for when a consonant has a vowel but what happens

when a consonant is instantly followed by another consonant? Such

consonants are called

Conjunct consonants where two or more consonants appear

together without a vowel between them. In English words like

street ("s", "t", "r" together),

spring ("s", "p", "r" together),

play ("p", "l" together) are a form of conjuncts.

For conjuncts in Devanāgarī, using Virāma is done almost exclusively

at the end of words whose last sound is a consonant. In other cases

we need to combine the two consonants in writing. This can be

achieved by omitting the right hand vertical element of the first

sign. Example:

maṇḍalaḥ -> circle

Here ṇ has no vowel and is followed by another consonant ḍ.

ण् ṇ + ड् ḍ = ण्ड् -ṇḍ-

मण्डल: -> circle

Let's look at another example:

ātmā -> soul

त् + म् = त्म् -tm-

आत्मा -> soul

Sometimes a letter does not have a vertical element or cannot be

combined with the next letter for some reason. In such cases letters

are made smaller and stacked on top of one another.

- द् d + म ma = द्म dma

- द् d + भ bha = द्भ dbha

- द् d + य ya = द्य dya

- द् d + व va = द्व dva

- प् p + त ta = प्त pta

- ड् ḍ + ड ḍa = ड्ड ḍḍa

Devanāgarī: The modern face of Sanskrit

The word Devanāgarī is formed by combining two words: deva (देव) meaning a male deity or divinity and nāgari (नागरी) which is an adjective derived from nagara (नगर) meaning town or city which can be used to talk about an urban city. Perhaps it was named as the script was associated with religious texts but Sanskrit had a larger atheistic literature than exists in any other classical languages including Greek, Latin, Arabic, Chinese, etc. So Devanāgarī being the script of the divinity does not hold true in any sense. The exact meaning of the word is unclear as to why was the script named this way.

Devanāgarī today is used to write 3 major languages: Hindi (more than 500 million speakers), Marathi (around 80-90 million speakers), and Nepali (around 15 million speakers). As we have seen above, Sanskrit in its lifetime was written in many different scripts but in the modern era Sanskrit texts are printed and shared mostly in Devanāgarī. So, the question arises why Devanāgarī?

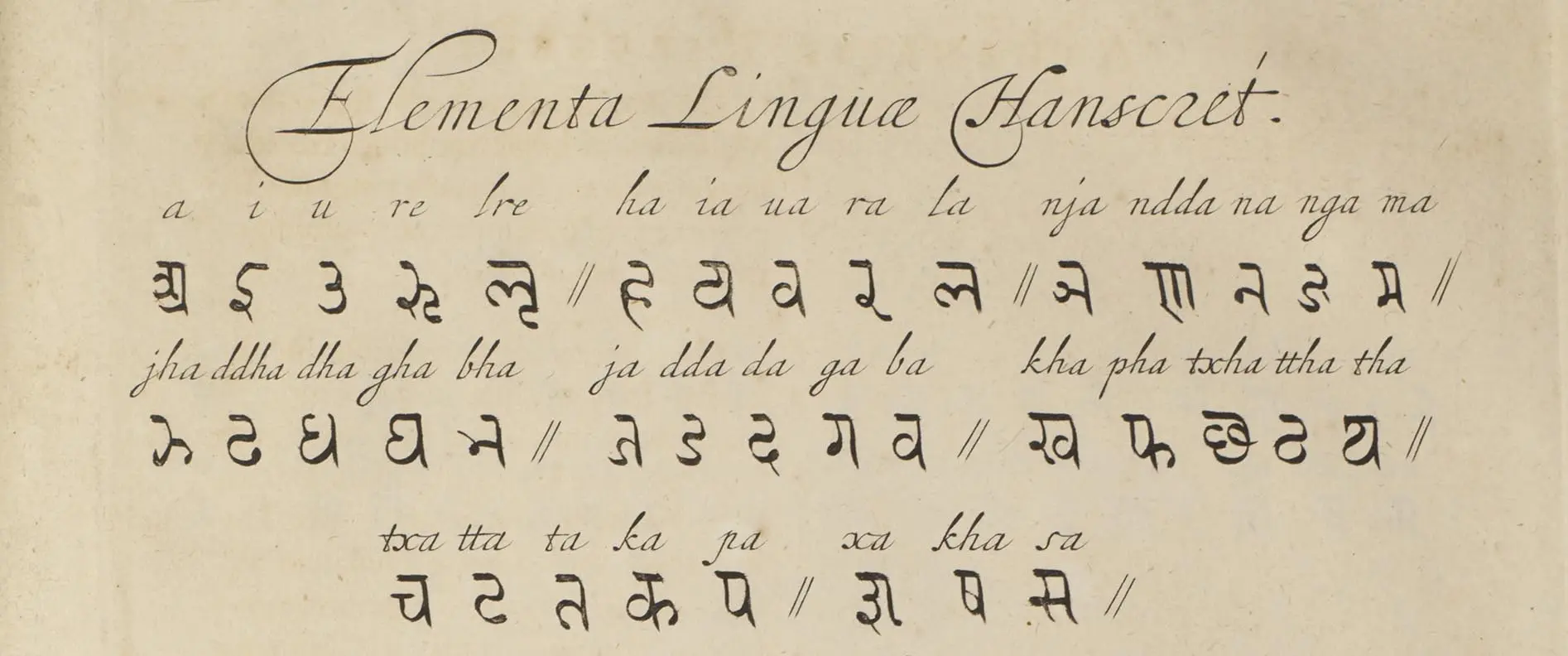

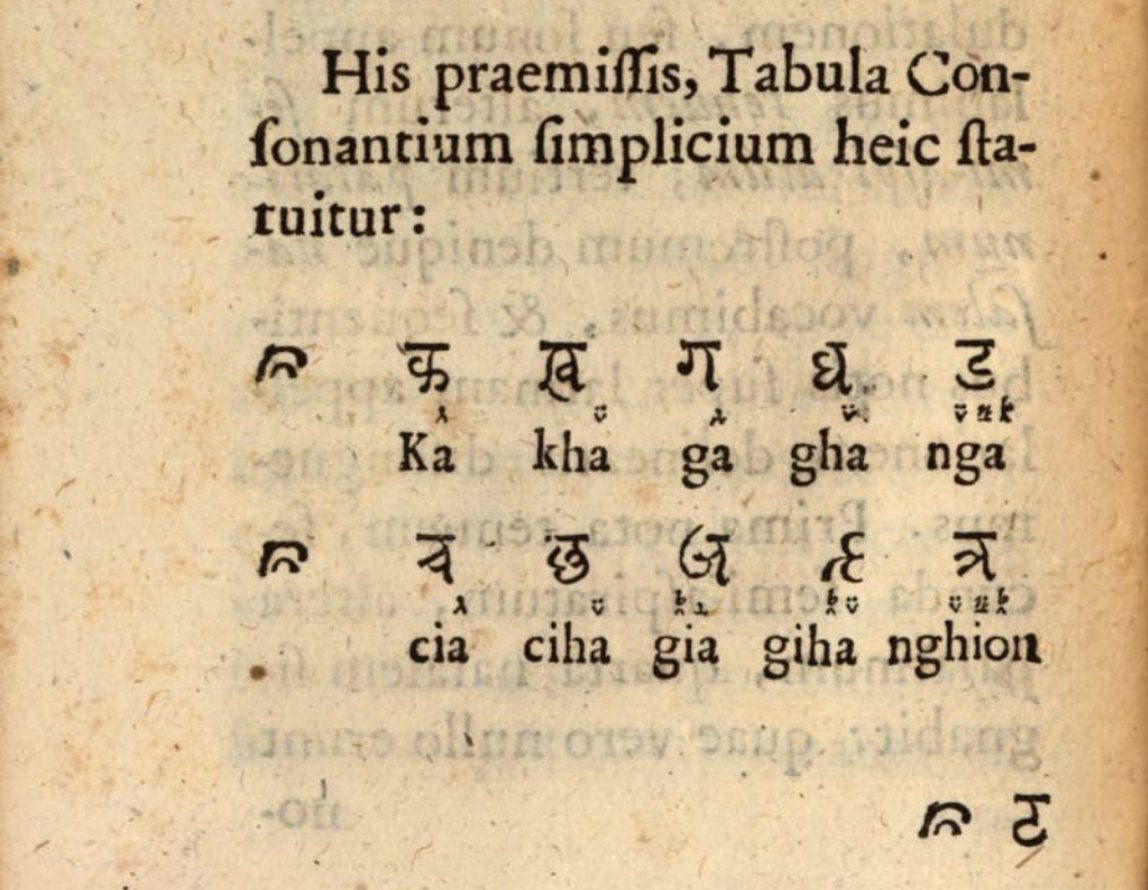

Early European Printing

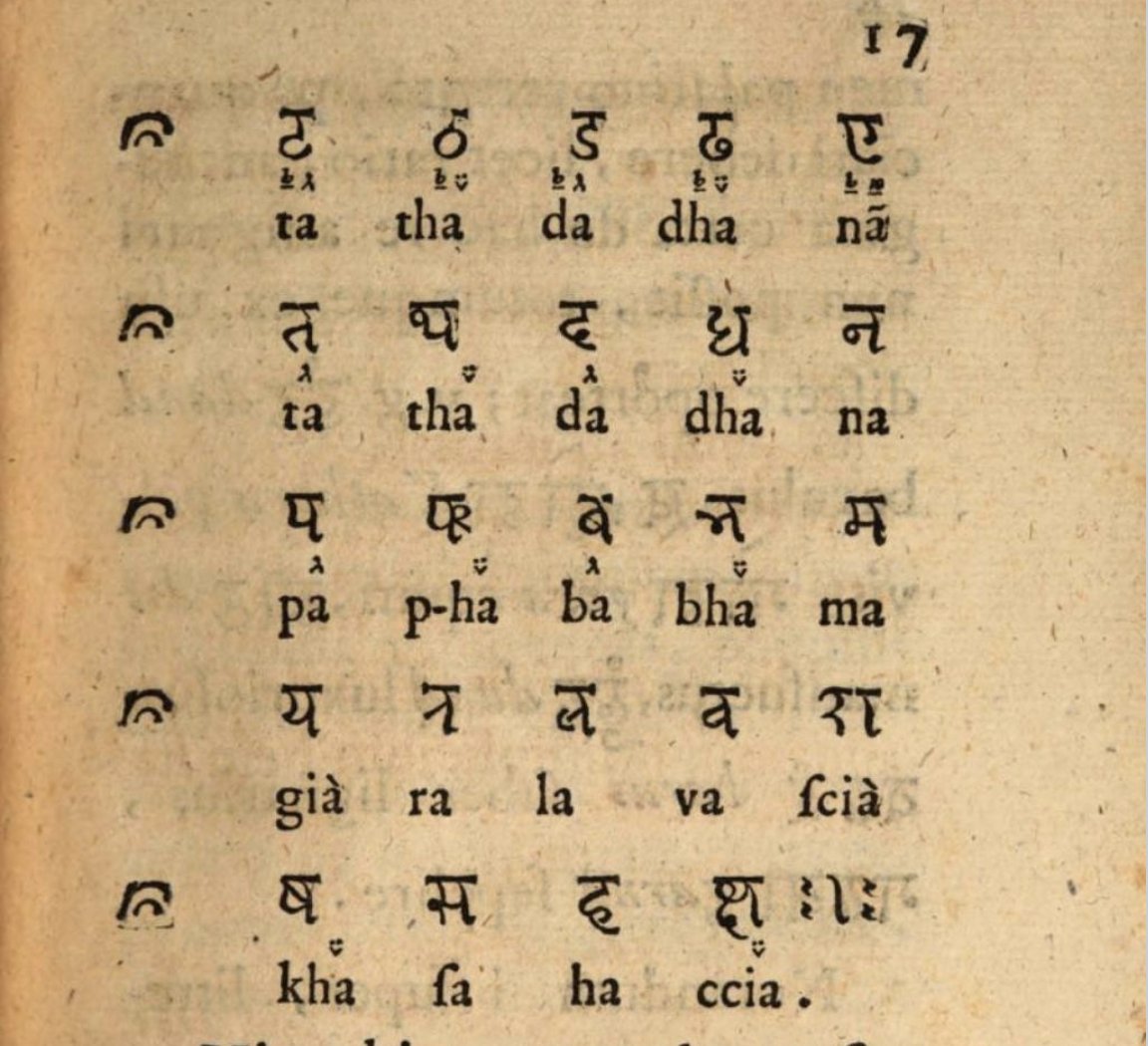

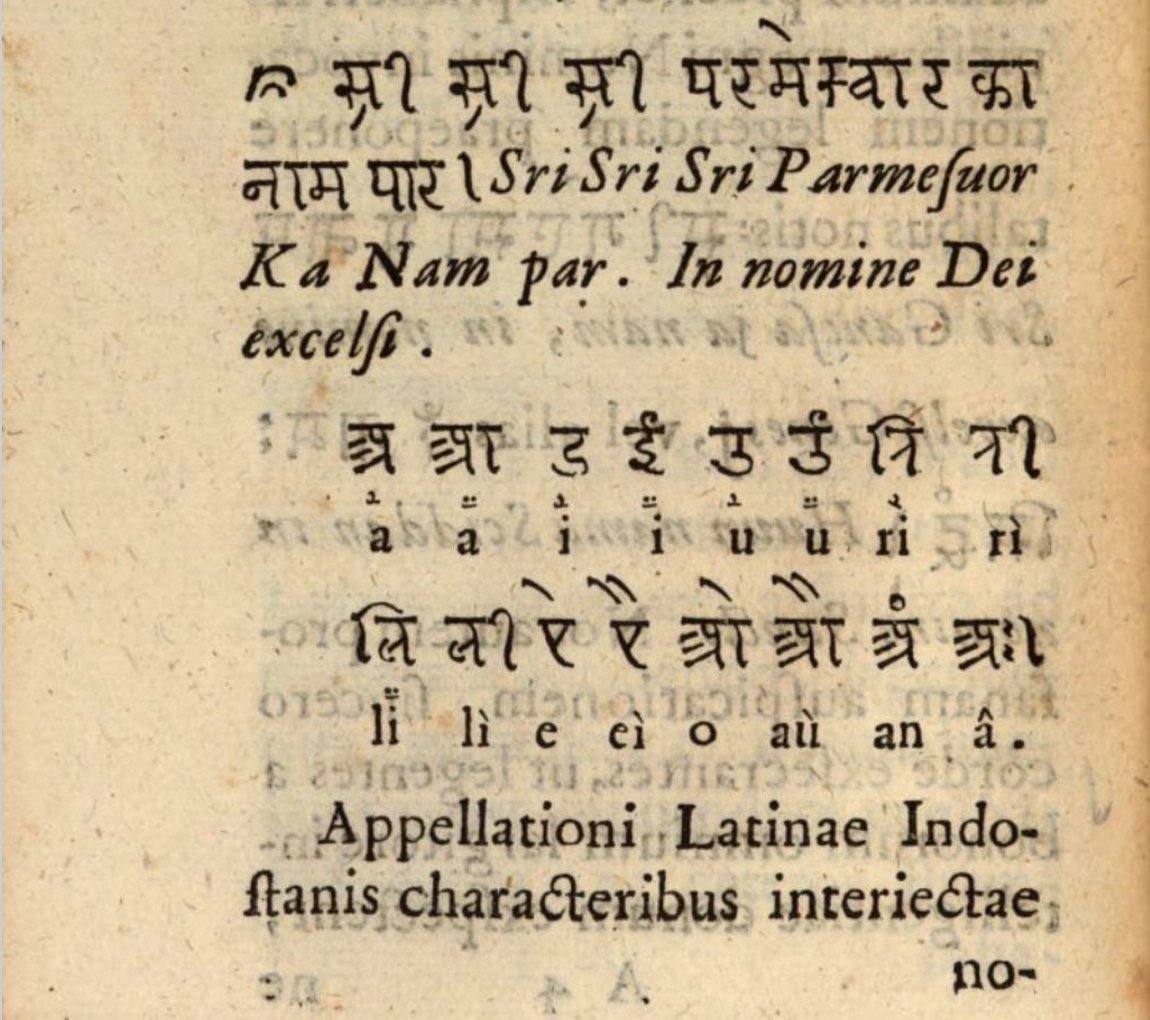

Indian literary traditions historically were largely oral where writing played a secondary role. Most written records from the pre-modern era were in the form of inscriptions and manuscripts. Despite the established and highly cultivated manuscript tradition of India, typography was a European import to the region and the technology was designed around the Latin script. Latin centrism led to modifications in the stacked conjuncts and vowel diacritics as they were easier to represent linearly in typography. The earliest evidence of printed Devanāgarī comes from the 1667 book China Illustrata published by German Jesuit Athnasius Kircher which compiles 17th century European knowledge on the Ming era Chinese empire and its neighbouring countries which includes India. He himself had never been to China but compiled the oral and written reports from former Jesuit missionaries to publish the knowledge on China and Tibet. However, the Devanāgarī in the book was printed using woodblock engraving and not metal movable types.

The first ever book printed in Devanāgarī was

Alphabetum Brahmanicum published in 1771 by

Cassiano Beligatti an Italian missionary.

We do not have any documented evidence on the development of the

casts used in the printing of this book.

Although Portuguese had begun printing in India around middle of the 16th century, they did not use Devanāgarī type and font for printing. Metal font casting in Devanāgarī was carried out mostly in Europe by Germans and British scholars. Devanāgarī printing in India would have to wait a few centuries until the end of 18th century.

British Calcutta and the First Indian Typefaces

When the British arrived in India, they had 3 cities in mind to setup their base - Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. Mumbai was under the Portuguese control and also made them vulnerable to resistance from Marathas who were at that time the strongest opposing force in the country. Chennai was too far from the north so would have been a difficult place to setup a trade base. Kolkata, named Calcutta by the British however had a weak Mughal ruler Siraj-ud-Daulah. After the British East India Company gained control of Bengal in 1757, they established Calcutta (Kolkata) as their administrative center. This made it the hub for European study of Indian languages. The East India Company transitioned from traders to landlords gaining control of all Bengal. The defeated Indian rulers were forced to sign the treaty, granting the East India Company Divāni rights, which allowed them to collect revenue from the territories of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa on behalf of the Mughal emperor. Kolkata was rich and educated with significant advantages. The area provided abundant supply of fertile land, fish, and meat. The river Ganga opened the floodgates of opportunities by setting up ports for business through the river which connected to the Bay of Bengal. They could also build inroads without bothering Portuguese who controlled Mumbai, Goa, Cochin, and Pondicherry. Hence, Kolkata became the capital of the British trade company. The Company's transition from traders to rulers meant they needed to understand local languages for administration. This is why European scholars began studying Bengali and Sanskrit in Kolkata not out of pure academic interest, but colonial necessity.

This concentration of wealth, power, and trade made Kolkata the natural center for European scholarship in India. And when scholars wanted to study Sanskrit and Bengali, they needed printing presses which meant they needed Indian craftsmen who could create the types.

Soon Europeans who would come to Kolkata began to study the local culture and languages. Sir William Jones a British philologist and a judge who served in Kolkata founded the famous The Asiatic Society to enhance and further the cause of Oriental research which in this case was India and its surrounding region. Some of the early members were Charles Wilkins and Alexander Hamilton. In his famous Third Anniversary Discourse to the Asiatic Society delivered on February 2 1786 he made the groundbreaking observation about the relationship between Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin. His famous statement was:

"The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have spring from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists: there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothick and the Celtick, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit, and the old Persian might be added to this family, if this were the place for discussing any question concerning the antiquities of Persia."

An important note: Jones was not the first one to make this observation. As early as 1653, Dutch scholar Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn had published a proposal for a proto language and in 1767 the French Jesuit Gaston Laurent Coeurdoux had demonstrated the analogy between Sanskrit and European languages. However, Jones' discourse is often cited as the beginning of comparative linguistics.

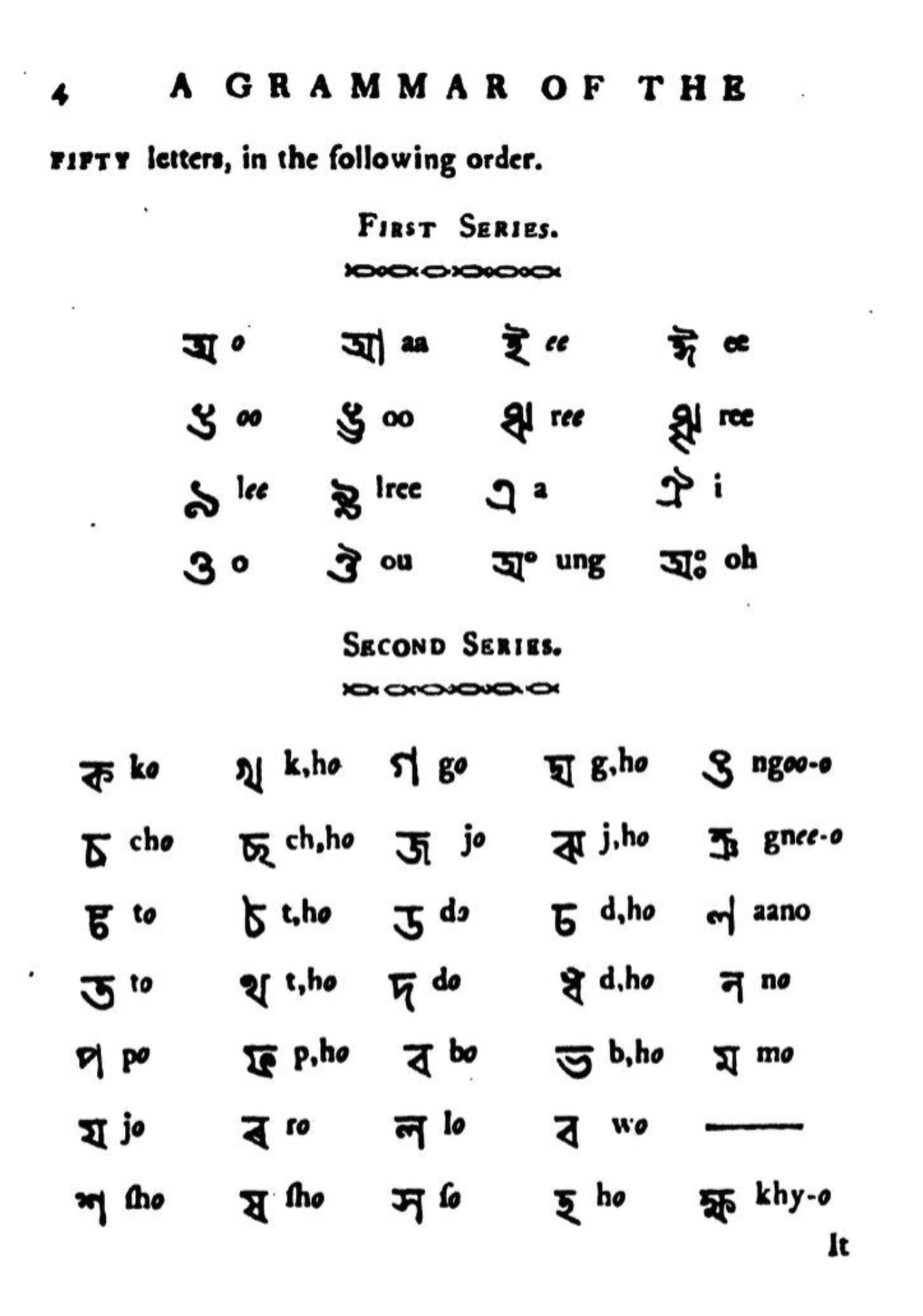

Although, Bengal had its own script - Eastern Nagari script also known as Bengali-Assamese script, the British expanded further west into Hindustani speaking territories making 'Hindustani' texts part of their research in Kolkata. Few East India Company officials (EIC) like English Orientalist Nathaniel Brassey Halhed had already learned the Bengali language and wanted to print a book on the Bengali grammar but couldn't because there were no typeface available. Enter Charles Wilkins (co-founder of Asiatic Society) and Bengali blacksmith Panchanan Karmakar who developed the first ever metal cast for Bengali in 1778. Along with the Bengāli types they also worked on creating Persian types. The significant stride made was in 1778 with the book A Grammar of the Bengal Language by Halhed printed in the press of a Mr. Andrews at Hooghly, a small town about 25 kilometers from Kolkata. Wilkins designed the typeface and Karmakar physically cut the punches and cast the type. There were two very brief phrases in Persian script in this book which was printed using the Persian types.

Pañcānana Karmakāra is considered the father of Bengali typography. The Karmakāras were a family of skilled metalworkers and calligraphers based in Tribeni, Hooghly, known for inscribing names and decorations on copper plates, weapons, and metal vessels. One of Pañcānana's ancestors earned the title Mullick from Nawab Alivardi Khan for his exceptional craftsmanship in carving sword and shield designs a testament to the family's generations of expertise in metalwork.

The Serampore Mission Press

Charles Wilkins came to Bengal in 1770 as a clerk working for the EIC and was the first Englishman to learn Sanskrit. He also translated Hitopadeśa, Bhagavadgītā, and Śakuntalā into English. Around 1778, inspired by his friend Nathaniel Brassey Halhed Wilkins began studying Sanskrit. He found "a Pandit of a liberal mind" who helped him learn Sanskrit though he didn't name this teacher. Later he moved to Vārāṇasī, the greatest center of traditional Hindu learning in India to work with the best Sanskrit scholars and met Paṇḍita Kāśīnātha Bhaṭṭācārya to teach him the inner workings of the language. At this point no Sanskrit-English dictionaries existed so Kāśīnātha compiled fundamental reference works for Wilkins with a list of Sanskrit verb roots called Dhātumañjarī meaning "Garland of Roots". Wilkins translated the Gīta while in India (1784), and it was published in London (May 1785) while he was still in India. Wilkins returned back to England in 1786. Although In the year 1795, residing in the countryside England, he began to arrange his materials on his learning of Sanskrit language and prepare them for publication. He cut letters in steel, made matrices and moulds, and cast from them a fount of types of the Devanāgarī characters, all with his own hands. Unfortunately, on the 2nd of May 1795, his house burnt down and he lost the typefaces in the fire, but luckily he was able to save all of his books, manuscripts, and most of the punches and matrices. Wilkins gave up on the idea of publishing his grammar, but the establishment of the East India College at Haileybury in 1805, which required Sanskrit instruction, encouraged him to resume the project. He had new types cast from his saved matrices and published his Grammar of the Sanskrita Language in London in 1808.

Meanwhile, Karmakar continued working on improving the Bengāli metal types as seen in the book Iṅgarāji o Vāṅgāli vokebilari published by Aaron Upjohn to help English speakers and beginners learn the Bengāli language where the typeface was different compared to Halhed's book.

Printing in Bengal was more of a political matter where books on Bengāli were printed to promote administrative efficiency in the EIC, the needs of religion actually helped further the cause of printing. Towards the end of the 18th century EIC decided to steer away from the missionary activity and forbidden it among the confines of the Company's Indian dominions. William Carey a worker of the Baptist mission arrived in Kolkata on November 11, 1795. Since EIC had banned missionary work he had to carry his work in secret. He knew that to fulfill his missionary work he needed to have an immense knowledge of the local language and hence he started learning Bengāli to translate the New Testment and completed the first translation by 1797. To adequately translate the Christian scriptures he also started learning Sanskrit. In a letter written in 1798 he wrote:

"I am learning the Sanskrit language, which, with only the helps to be procured here, is perhaps the hardest language in the world. To accomplish this, I have nearly translated the Sanskrit Grammar and dictionary into English, and have made considerable progress in compiling a dictionary, Sanskrit including Bengali and English."

After completing his New Testment translation he started looking for ways to publish it. He procured a wooden printing machine for £40 but obtaining Bengāli alphabet types was more difficult. Initially he planned to get punches of the Bengāli alphabet from London but it proved to be a too costly approach. He learnt about a foundary (a type making factory) but couldn't trace the whereabouts of the factory. In this process he did learn about a technician who had received training in the art of making types of Indian alphabets from Sir Charles Wilkins and was available for employment. This technician was of course Pañcānana Karmakāra. Carey went on to publish multiple books in Bengāli.

In the beginning of 1799 Carey was joined by 2 other missionaries to assist him and they moved to the Danish settlement of Serampore as they couldn't find a settlement in Company's dominion of Kidderpore. Here he started the Serampore press with the other 2 missionaries. An extract from a letter written by him dated February 5, 1800:

"The setting up of the press would have been useless at Mudnabatty, without brother Ward, and perhaps might have been ruined, if it had been attempted. At this place, we are settled out of the Company's dominions and under the government of a power very friendly to us and our designs."

A historian of the mission work asserts that the Karmakāra met Carey only after they had settled down at Serampore. He writes:

"At the beginning of 1803, the missionaries had made considerable progress in the preparation of a fount of Deva Nagree types. The Deva Nagree is the parent of all the various Indian alphabets, and, according to the mythological tradition, the special gifts of the gods. This was the first fount of this type which had been attempted in India. Soon after the establishment of the press at Seerampore, the native blacksmith Punchanon, who had instructed the art of punch cutting by Sir Charles Wilkins, came to the Missionaries in search of employment. Mr. Carey was then contemplating a Sanskrit Grammar, for which it was necessary to obtain Nagree types, and Punchanon was immediately engaged for the work."

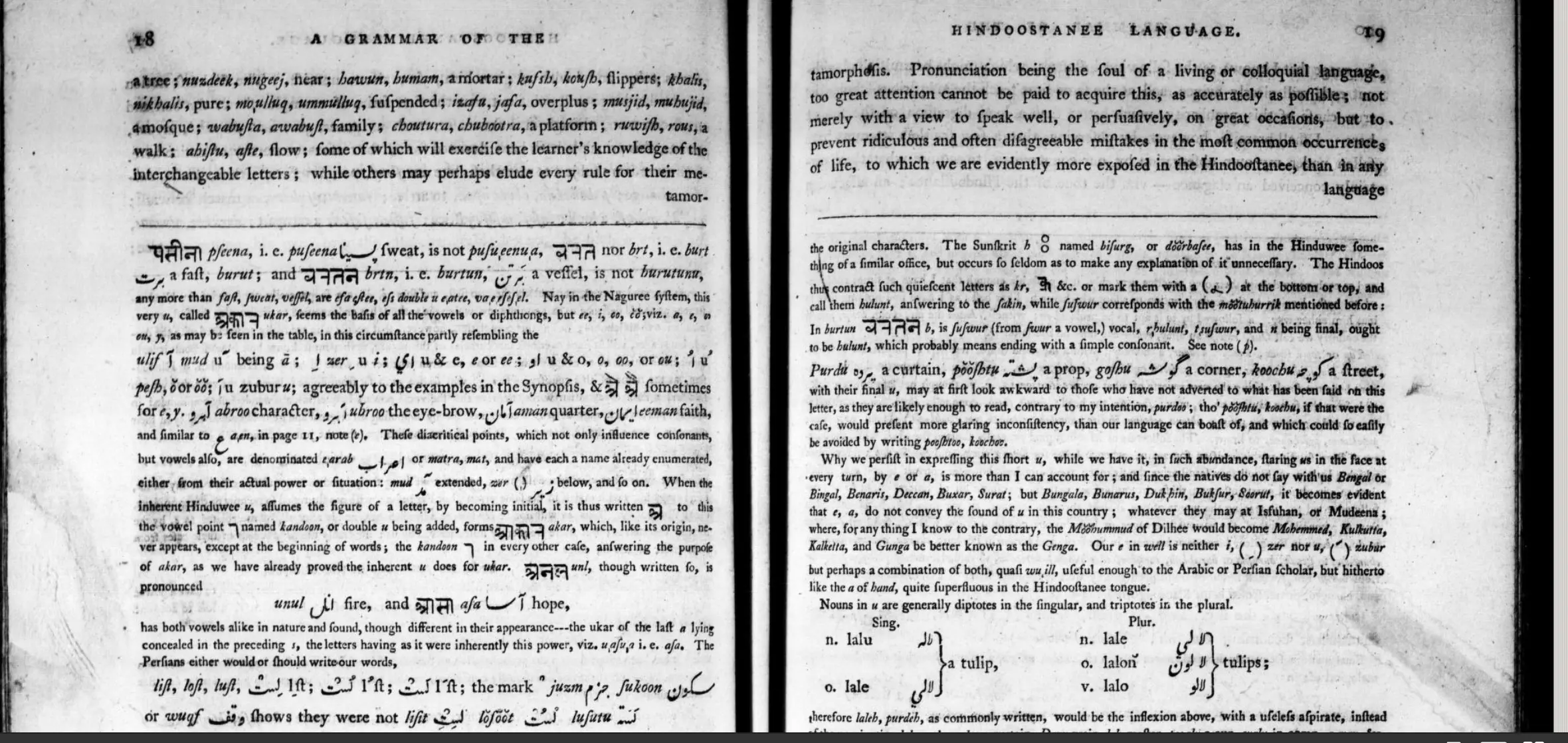

In 1801 Carey was appointed as the professor of Bengāli and Sanskrit at the Fort William College of Calcutta. This made his attention turn to printing books on non-religious subjects for the use of his students. It was due to this that he asked Karmakāra to work on creating types for Devanāgarī so he could print his book A Grammar of the Sungskrit Language which required almost 700 separate punches. Towards the end of 1804 Hetopudes (Hitopadeśa), the first Sanskrit work to be printed was published making this piece the first full Devanāgarī work to be published. Unfortunately, I couldn't find a copy online since the book is rare and there's no digital copy available anywhere on the internet. He also published a Marathi Grammar book using Devanāgarī types but eventually moved to the Modi script types which was being used to write Marathi in Maharashtra.

Although Charles Wilkins had prepared the Devanāgarī types script as early as 1795, his book on the Sanskrit grammar was not published until 1808. In fact Carey's grammar books on Marathi was published in 1805 and his grammar book on Sanskrit was published in 1806. There is a book in the National Library Kolkata, called Grammar of the Hindustanee Language by John Gilchrist, printed at the Chronicle Press in Calcutta in 1796 which uses Devanāgarī types. This is probably the earliest instance of Devanāgarī printing in India but uses wooden movable types instead of metal.

Colonial Impact on Modern Devanāgarī

This style of printing Devanāgari had a huge impact on the language. Europeans introduced Western style punctuations and spacing into their printed texts something that caught on and remains to this day. Traditional Sanskrit manuscripts used scriptio continua (continuous script without word spaces) and ancient grammars like Pāṇini's traditionally omit spaces between words with segmentation guided by Sandhi (more on Sandhi in a different article) rules that alter sounds. Traditional Devanāgari used only 3 punctuations marks

- daṇḍa ( । ) - marks end of sentence or middle of verse

- double daṇḍa ( ॥ ) - marks end of paragraph or verse

- avagraha ( ऽ ) - marks vowel elision in sandhi

But modern Devanāgari texts make use of various English punctuation marks including exclamation marks, commas, question marks, etc. Conjunct formation was simplified compared manuscripts and inscriptions forms which reduced the number of unique types needed lowering costs as well. The famous Indologist William Jones declared Devanāgari to be the most ideal scripts for Sanskrit which was appreciated by Wilkins and later by the German Indologist Max Müller.

With the advancements in the printing technology, it was still almost entirely an European endeavour - missionaries, the colonial state, and European entrepreneurs. As some scholars note, Indians only provided labour and received training in the various processes of typography. The primary readership of these European run presses was also European. Indians were just useful informants that helped guide the European type designers but were not the active drivers of the process.

The Colonial Legacy: How Standardization Changed Sanskrit

The British decision to standardise on Devanāgarī had lasting effects:

- Loss of regional diversity: Before printing, each region used their familiar script. After standardisation, regional scripts declined for example: the Modī script used for writing Marāthi.

- The "Devanāgarī = Sanskrit" myth: Today, most people think Devanagari is "the" Sanskrit script. But this is only 200 years old a colonial creation.

- Simplified typography: Many traditional conjuncts were simplified or eliminated to make printing easier.

- Western conventions: Punctuation, spacing, and layout conventions from Latin printing were imposed on Sanskrit texts.

Conclusion

So, why did Sanskrit become script agnostic? Because Sanskrit was primarily oral for so long, when regions started writing it, they used whatever script they already knew. There was no central authority dictating "Sanskrit must be written THIS way". This means you can learn Sanskrit in any script as long as you understand the fundamentals of the language.

Can different scripts affect pronunciation? Short answer: No, they're just different ways to write the same sounds.

Are texts translatable between scripts? Yes, completely! Same language, just different "clothes".

The standardization on Devanāgarī created the modern myth that it's "the" Sanskrit script. But Sanskrit's script agnostic nature persists. You can still learn Sanskrit in any script—the sounds remain the same, only the visual representation changes. Here's what's remarkable: these scripts are just different ways to write the same sounds. The word 'namaste' looks completely different in each script, but it's pronounced identically:

- Devanāgarī: नमस्ते

- Bengali: নমস্তে

- Tamil (Grantha): நமஸ்தே

- Kannada: ನಮಸ್ತೇ

- Thai: นมัสเต

- Khmer: នមស្តេ

Same word, same pronunciation—just different visual systems.

In the next article we will listen to the phonology of Sanskrit.