Welcome to the ध्वनि blog.

ध्वनि the Sanskrit word for sound: from Proto-Indo-Aryan *dʰwaníṣ, from Proto-Indo-Iranian *dʰwaníš, from Proto-Indo-European *dʰwen- (“to make a noise”).

I am putting down all my thoughts and learnings from my journey into modular synthesizers. I am a software engineer by profession and have been exploring sounds for the past spending a lot of time just reading and researching on the topic.

Let's start with some basics first.

"How did you know how to do that?" he asks.

"You just have to figure it out."

"I wouldn't know where to start," he says.

I think to myself, That's the problem, all right, where to start.

To reach him you have to back up and back up.

And the further back you go, the further back you see you have to go,

until what looked like a small problem of communication turns into a major philosophic enquiry.

- Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

What is sound?

Sound is nothing but a result of pressure variations in the air (or any medium), caused by disturbances such as vibrations in our surroundings. For eg. if you hit a tuning fork it creates a disturbance in the air pressure and when that disturbance reaches us our brains translate that change in pressure to sound. Sound is a natural acoustic phenomenon of vibrations moving usually through air (or any kind of medium) to our ears.

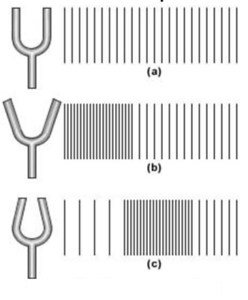

Ok let's try to visualise what happens when a tuning fork is hit.

When the prongs of a tuning fork vibrate, they disturb the air particles around them. When the prongs move apart, they push against the neighboring air particles, causing compression. In this compressed region, the particles are forced closer together, increasing the air pressure. This compression represents the "push" of the wave but does not involve air particles traveling with the wave only their vibrations about their mean positions. When the prongs move back to their original position, the compressed air expands, causing the air particles to move slightly away from each other, resulting in rarefaction a region of lower pressure. The particles return to their original positions but continue to oscillate, contributing to the wave's propagation. Air particles don't move with the sound wave because sound is a mechanical wave (meaning it needs a medium to travel), and mechanical waves transfer energy, not matter. Sound is a pressure/compression wave.

Because of this motion of the air particles due to the vibrations from the tuning fork there are regions where the air particles are compressed together and other regions where the air particles are spread apart. These regions are called compressions and rarefactions respectively. The alternate compression and rarefaction form on the same point, there is no migration of the particles. Sound results from this mechanical wave caused by the back and forth movement of the particles through a medium.

If you could see sound waves, it would look more like what happens when you blow up a large beach ball. Imagine that you blow into a beach ball and it expands outwards in a spherical shape. When you take your mouth off the nozzle to take another breath the ball slightly deflates. As you blow the next breath into it the ball expands again and slightly deflates when you take the next breath, and so on until the ball is completely inflated. In a similar manner sound propagates away from the source in a sphere moving outward and then recoiling inward and then outward and so on.

How do we perceive sounds?

On the level of physics what we call sound is a vibration or referring an old word verberation. This is a wave that following the shaking movement of one or more sources propagate and reaches our ears where it gives rise to auditory sensations. Physically speaking sound is the shaking movement of the medium in question. Sound propagates in concentric cirlces similar to ripples seen on throwing a rock into calm waters. In the air the verberation propagates at a speed of approximately 343 meters per second. It was only at the beginning of the nineteenth century that this average speed of sound which varies slightly relative to pressure and temperature was able to be calculated. In water the wave propagates considerably faster (1500 m/s). Sound also travels through hard material and this is the reason why it is so hard to soundproof apartments that are located on top of the other. Sound in the physical sense has only two characteristics: frequency the number of oscillations (or vibrations) per second and pressure amplitude which correlates to the magnitude of the oscillation. Frequency is perceived as pitch and the amplitude is perceived as sonic intensity (loudness). All of the other perceived characteristics of sound are produced by variations of frequency and amplitude over time. The sound propagation takes place in every direction and it weakens in proportion to the square of the distance traveled. There is a reflection when the verberation encounters a surface that does not absorb it completely and returns a portion of it like a bouncing ball. Weh we hear sound via direct propagation from the source and a reflected sound the lag between the direct sound and reflected sound combine to produce reverberations. When a sound wave encounters an obstacle a portion will bypass it and this is called diffraction. Diffraction is what makes acoustic isolation difficult to achieve.

The ears detect, analyse, and classify biologically interesting sounds and construct a model of auditory scene that surrounds us. The auditory system is attuned not only to listen to certain sounds but to ignore sounds that are not biologically relevant. Such sounds include ambient noises and the effects of sound reflection, refraction, diffusion which can distort the incoming sound. Imagine that you stretch a pillowcase tightly across the opening of a bucket and people throw balls at it from different distances. Each person can throw as many balls as they like and as often they like. Now your job is to figure out just by looking at how the pillowcase moves uop and down, how many people are there, who they are, and whether they are walking towards you, away from you or are standing still. This is what our auditory system has to do when making identification of auditory objects in the world using only the movement of the eardrum as a guide. (Of course the brain combines the data received through the eyes to form a holistic model of the current environment.)

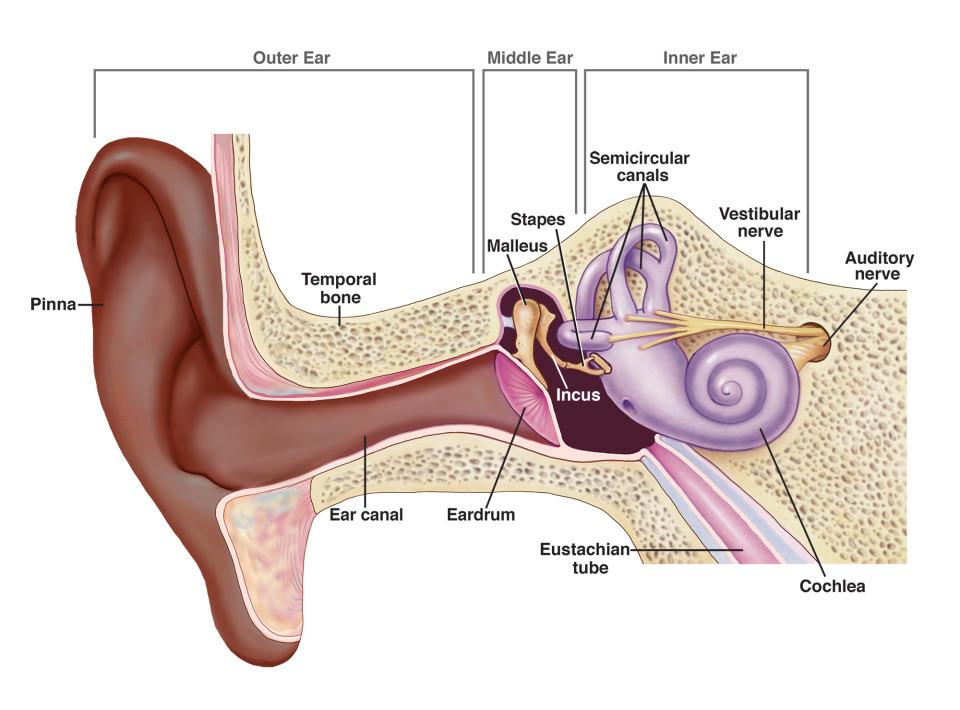

Human ear is an organ which is external and internal at the same time. The ear as an organ is divided into outer, middle and inner. The outer ear consist if the pinna, the auditory or the ear canal and the eardrum. Pinna helps with protection (from wind and other things that might interfere with audition) and resonance. The funnel shaped pinna collects sound from the environment and its shape modifies the arriving frequency information depending on the direction of the source. The pinna directs the waves towards the tympanic membrane and its form favours frequencies that we use in verbal communication. The ear canal of the human adult is on average 7 to 8 millimeters in diameter and 2.5 to 3 centimeters deep. Its structure also tends to attenuate sounds that impede verbal communication mainly bass frequencies. Frequencies around 3000Hz are transferred more efficiently by the canal and we are more sensitive to this range of frequencies. The eardrum is bent by the force of arriving sound and transmits the motion to the middle ear. It vibrates more easily between 1-3.5kHz frequency range but transmits sounds to the inner ear over the entire audible frequency range. The ear drum and the middle ear play a crucial role in overcoming the mismatch between the low density air in the outer ear and the much of the denser fluid in the inner ear with a process called impedance matching. Impedance refers to the resistance a medium offers to the flow of energy. Air has low impedance while the fluid in the inner ear has high impedance. Without a mechanism to fix this mismatch sound waves sound waves mostly be reflected back when they hit the fluid in the inner ear. This would reduce the amount of sound energy entering the inner ear making hearing inefficient. Normally, when sound travels from a low impedance medium like air to a high impedance medium like water almost all of the acoustical energy is reflected. We still have very low understanding of how the eardrum accomplishes this task over such a wide frequency range.

The middle ear is primarily made up of tympanic membrane and the series of tiny bones called ossicles that go by the names of "hammer" (incus), "anvil" (malleus), and "stirrup" (stapes). The bones function to transfer the pressure vibrations into mechanical vibrations which are passed along to the entrance of cochlea which is called the oval window. The tympanic membrane (eardrum) approximately one centimeter in diameter is an elastic membrane is in contact with these ossicles. This series of little bones transmit the vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the inner ear while amplifying the frequencies between 1000 and 4000Hz. It is here that the bones protect against the sounds that are too loud with a mechanism called acoustic reflex (also called the stapedius reflex or middle ear reflex). Not only does this mechanism protect us from loud sounds, it also dulls the loudness of our own voices when we speak. It involves tiny muscles attached to the ossicles that respond to the loud sounds by reducing the movement of the bones thus limiting the amount of energy transmitted to the inner ear. The stapedius muscle and the tensor tympani muscle contract reflexively with in 10-20 ms in response to loud sound pressures exceeding 70-100dB SPL (Sound Pressure Level). When these muscles contract they dampen the movement of the ossciles which stiffens the ossicular chain reducing the transmission of the sound vibrations reaching the inner ear. By stiffening the ossicles, the reflex reduces the intensity of the sound that reaches the cochlea by approximately 20 decibels.

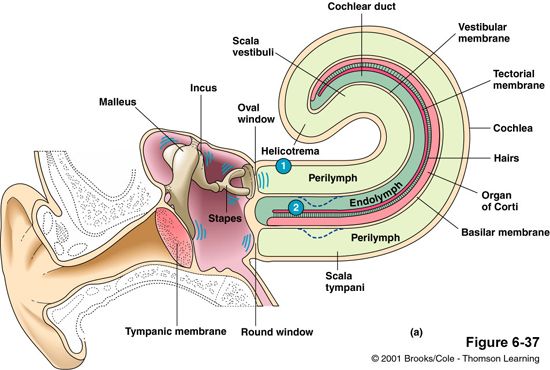

The inner ear consists of organs that help with balance and audition. The audition is handled by cochlea Greek for "snail" due to its coiled shape. The stapes connects to the oval window at one end of the cochlea a fluid filled tube that connects to the auditory nerve. The other end is called a round window. The side of the oval window is called the scala vestibuli and the side of round window is called scala tympani The two scala are filled with perilymph a fluid similar to spinal fluid. The vibrations from the stapes to the oval window moves the fluid back and forth. The round window has a flexible membrane and acts as a pressure release point bulging outward when the fluid moves. The two scala enclose the scala media filled with endolymph which is similar to intracellular fluid. Within the scala media is the organ of Corti which rests on the basilar membrane and contains specialised sensory cells called hair cells. It includes 3 rows of outer hair cells and 1 row of inner hair cells.

The basilar membrane runs down the center of cochlea. About 30,000 hair cells are attached to it along the length. (Note: this is the same hair cells we talked about in organ of Corti). The membrane is thinner at the base close to the oval window and round window. This thinner end vibrates more at high frequencies than its thicker end which is at its apex. Low frequencies vibrate the perilymph more intensely at the apex of the membrane. The position along the membrane encodes frequency required for audition.

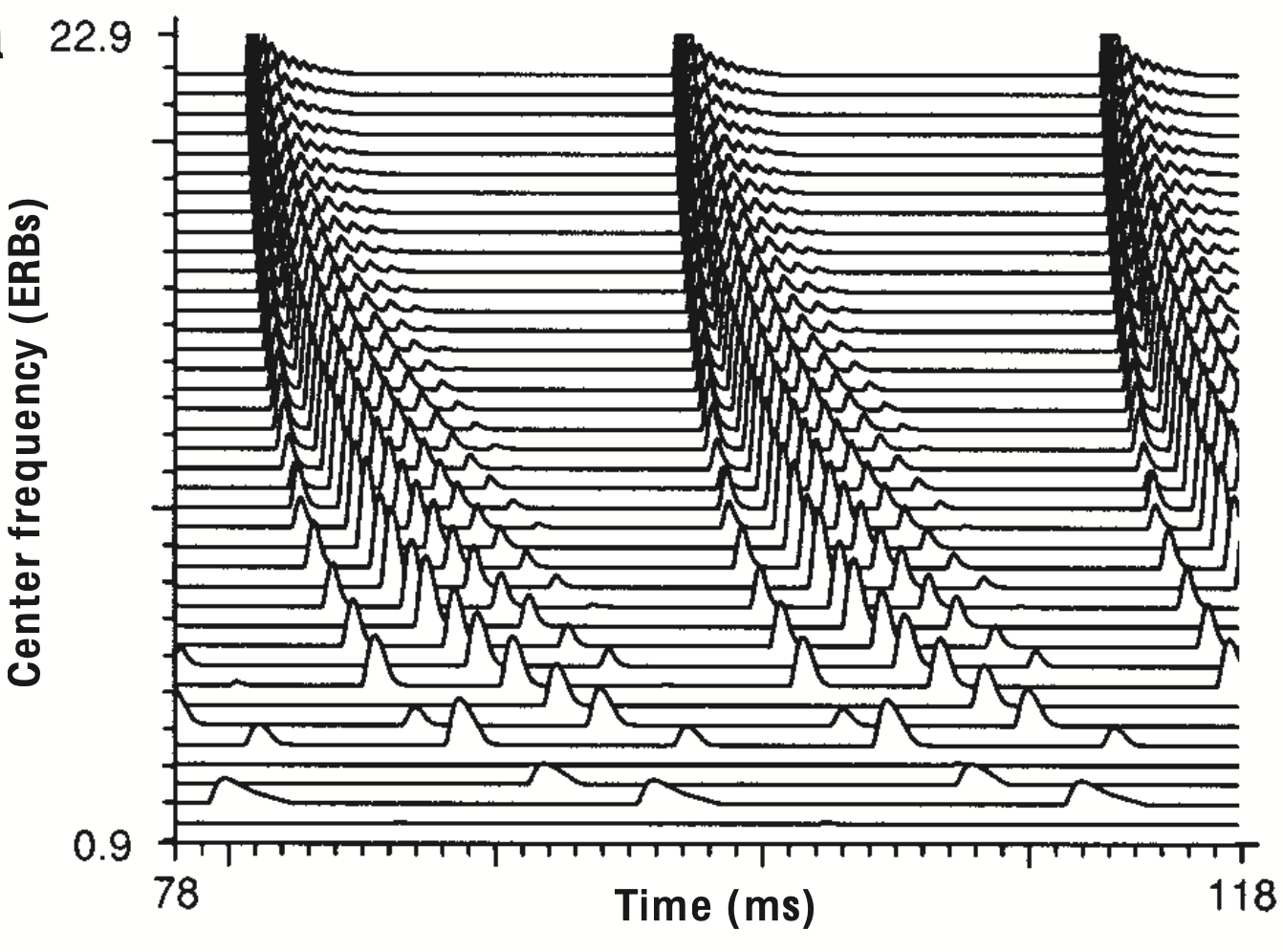

A short sample of the neural activity pattern with time (in ms) vs the length of cochlea (in cm) produced by the cochlea in response to a musical note composed of all the harmonics of 62.5Hz. The graph shows the temporal microstructure of the neural response of the cochlea's analysis of the sound.

As the membrane moves it causes the hair cells in the organ of Corti

to bend. The top of these hair cells have tiny hair-like structures

called stereocilia. When these bend they

open ion channels leading to an electrical signal being generated.

There are mechano-sensitive ion channels at the tips of the

stereocilia and these channels are sensitive to mechanical

deformation. On bending the tips stretch which pulls the channel

open. This allows potassium ions (K

Ok so the ears have processed the pressure waves, turned them into electrical signals, and transmitted them to the brain but how does the brain turn these signals into sound? Let's try to make sense of that by taking the example of music (organised sound).

The human brain is divided up into four lobes: the frontal,

temporal, parietal, and occipital plus the cerebellum. The temporal

lobe is associated with hearing and memory. The cerebellum, the

oldest evolutionary part of the human brain going back to the

reptilian brain is involved in emotions and the planning of

movements. Different aspects of the music are processed by different

parts of the brain and the brain uses functional segregation for

processing it and uses a system of feature detectors to analyse

specific aspects like pitch, timbre, tempo, etc. Brains are complex

computational systems and networks of interconnected neurons perform

computations which leads to thoughts, perceptions and ultimately

consciousness. The average brain consists of one hundred billion

(100,000,000,000) neurons, this is a lot of neurons but the real

complexity arises through their connections. The formula for how n

number of neurons can be connected to each other is 2(n* (n-1)/2).

For 2 neurons there are 2 possibilities for how they can be

connected

For 3 neurons there are 8 possibilities

For 4 neurons there are 64 possibilities

For 5 neurons there are 1024 possibilities

For 6 neurons there are 32,768 possibilities

The number of combinations possible for an average brain is HUGE!

Much of the computational power comes from this enormous possibility

for interconnections and the fact that brains are serial processors

unlike computers which are parallel processors.

This is how the auditory system processes sound: it doesn't have to wait to find out what the pitch of sound is to determine where the sound coming from. There are neural networks who dedicated to this process are separate. If one of the circuits is done processing it can send the information to other parts of the brain and they can start using that information. If the late arriving information affects the interpretation of the previous information our brains just "change their mind" and update the model of what they think of the incoming sound. This is called Predictive coding. As per the theory the brain constantly generating and updating the mental model of the environment to predict incoming sensory information. The theory is part of broader framework of Bayesian inference is the fundamental mechanism for perception, cognition, and action. The brain doesn't just passively receives information from the world but actively predicts it and uses incoming data to correct or refine its predictions.

How does the brain figure out from the disorganised mixture of

molecules beating again the eardrum what's out there in the

world?

The brain uses something called as

feature extraction followed by this

other process called

feature integration. The brain extracts

low level features using specialised neural networks that decompose

the incoming signal into information about pitch, timbre, spacial

location, loudness, etc. Frequency (pitch) is processed by specific

regions of the auditory cortex that correspond to different

frequencies, known as tonotopic organization. Neurons at various

levels in the auditory pathway are topographically arranged by their

response to different frequencies. This organization is referred to

as tonotopy or cochleotopy. The primary auditory cortex located in

the temporal lobe is tonotopically organised just like cochlea for

detecting the frequencies in the sound. Neurons in the different

regions of the auditory cortex are sensitive to specific

frequencies. Cells that respond to low frequencies are located in

one region of the cortex. Cells that respond to high frequencies are

located in another region. As we have noted previously the same

structure is followed by cochlea to detect the frequencies in the

sound. Volume (loudness) is perceived based on the intensity of

neural firing in response to the electrical signals. These

operations are carried out in parallel and can operate somewhat

independently of one another. This sort of processing where only the

information contained in the stimulus is considered by the neural

circuits is called bottom up (sensory) processing. In the brain

these attributes of music/sound are separable. The term low level

refers to the perception of the building block attributes of sensory

stimulus.

At the same time as feature extraction is taking place in the

cochlea, auditory cortex, and brain stem the higher level centers of

the brain are receiving a constant flow of information about what

has been processed so far and this information os continuously

updated and rewritten if needed. Centers for processing higher

thought mostly in the frontal cortex keep receiving these updates

and they working quickly to predict what will come next in the

music/sound. The enjoyment we experience from music stems from the

brain's ability to predict upcoming musical patterns, such as

rhythm, melody, and harmony. When these predictions are confirmed,

it creates a sense of satisfaction, making the music feel rewarding.

This interplay between expectation and fulfillment is a key reason

why music is so pleasurable to our brains.

The frontal lobe calculations are called top down processing and it

can influence the lower level circuits while they are doing bottom

up processing. The top down (cognitive) and bottom up (sensory)

processes communicate with each other in an ongoing fashion.

Features extracted at the lower levels are integrated at higher

levels to form a cohesive perceptual whole. Top down and bottom up

processing is one of the key concepts in predictive coding helping

us to form an accurate model of our surroundings.

The transformation of electrical signals into the conscious experience of sound in the brain is still one of the great mysteries of neuroscience. While much is known about the neural pathways involved in hearing the exact mechanism by which electrical signals are turned into the subjective perception of sound what we call qualia remains elusive. This phenomenon is part of the broader "hard problem of consciousness" a concept introduced by philosopher David Chalmers. But hopefully this article gives you a holistic view of how we perceive sound as soon as we start hearing it. I'll keep adding more stuff to this article depending on my further research into the topic.