Phonology of Sanskrit

Sound: The fabric of our reality?

Auṃ ॐ

As per the Hindu cosmogony, this primordial sound is what the supreme deity Brahmā who emerged from a lotus from the navel of lord Viṣṇu (विष्णु) uttered which generated the five great elements Pañcamahābhūta (पञ्चमहाभूत) :

- Ākāśa (आकाश): Ether/Space first element formed from the vibration of Aum.

- Vāyu (वायु): Air from ether's motion

- Agni (अग्नि): Fire from air's friction

- Jala (जल): Water when fire condenses

- Pṛthvī (पृथ्वी): Earth when water solidifies

The universe emerges from nāda (नाद) the primordial sound. Nāda Brahmā (नाद ब्रह्मा) i.e. the sound of creation is considered the foundation of existence.

Bhartṛhari (भर्तृहरि) was a Hindu linguistic, philosopher, and a poet circa 5th century CE. He is best know for his work Vākyapadīya (वाक्यपदीय) which is treatise on sentences and words. In the first verse of his book he states:

अनादिनिधनं ब्रह्म शब्दतत्त्वं यदक्षरम् ।

विवर्ततेऽर्थभावेन प्रक्रिया जगतो यतः ॥ १ ॥

anādinidhanaṃ brahma śabdatattvaṃ yadakṣaram |

vivartate'rthabhāvena prakriyā jagato yataḥ || 1 ||

"The Brahman who is without beginning or end, whose very essence is the Word, who is indestructible, who appears as the objects, from whom the creation of the world proceeds."

Across different cultures we see a similar phenomena. Christianity places a big emphasis on the power of sound through words.

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. Through Him all things were made; without Him, nothing was made that has been made."

In Christian worships practices, believers connect to the divine through hymns, psalms, and chants. Gregorian chant was foundational to early Western music influencing the development of polyphony, musical notation, sacred compositional traditions, etc.

The act of creation in Judaism too is linked to speech. Jewish tradition teaches that the world was created through ten divine utterances. The utterances from Genesis include "Let there be light" and other statements from God. The blowing of shofar a trumpet made from the horn of a kosher animal with the marrow removed during Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and at the conclusion of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) shows the significant role played by sound in Jewish rituals.

In Islam, the Quran describes the act of creation as. being initiated by the divine command Kun which means "Be". The full phrase is "Kun Fayakun" meaning "be, and it is". Appearing 8 times in the Quran, it symbolises the instantaneous nature of divine creation: when Allah wills something to exist, it exists immediately.

In Sikhism, Shabad (Divine Word) and Naam (Divine Name) are central to the creation of this world. Hukum (Divine Command/Will/Order) governs the creation. Guru Granth Sahib the holy scripture of Sikhism talks about the practice of Kirtan, the singing of hymns as a a form of devotion to foster a deep connection with the Creator.

Several Native American cultures believe that songs and sounds are not just tools for communication but are sacred and shape the world. The Hopi people identifies the role of singing in their cosmology where the Creator Taiowa first conceived the world and Sotuknang his nephew executed the creation through the power of sound and song. The Lakota people have ceremonies like the Sun Dance or the use of the Sacred Pipe with scared songs that are believed to sustain the cosmic order. The songs are believed to be "language of the spirits", allowing for a direct connection with the divine. For the Navajo people the Holy Wind (Níłch’i) is the source of all movement, breath and speech. Chanting in ceremonies is designed to re-align the individual with the Holy Wind to restore beauty.

In many African cultures drumming sounds, chanting and singing plays a big role in spiritual practice. The Dogon people of Mali of West Africa believe that Creator Amma, began the universe with vibrations and is often compared to the weaving process where sound and vibration are the threads that create the fabric of reality. These vibrations are symbolised by drums which is a sacred instrument that plays the rhythms of creation. The Yoruba people use Oriki, praise poetry to call forth the spiritual power of the ancestors into their physical realm. It is believed to carry the power of creation as it invokes the energy of the Orishas (deities). Across many African cultures, the drum is a scared instrument that bridges humanity to divine. the Djembe Drum is believed to carry the heartbeat of earth. The drumbeat is associated with the pulse of life.

In Chinese philosophy, Daoism (Taoism) and the concept of Dao (Tao) are tied to sound and vibration which is the ultimate principle that governs the universe. Sound and vibration are seen as manifestations of the Dao's flow and harmony. Japanese Shinto and Buddhist traditions too reflect the belief in the power of vibration and resonance. In Shinto Kotodama "the spirit of words" empahsises that spoken words carry spiritual power.

Ancient Egyptians and Greek had similar outlook of sound being the force in the creation of this universe. As per the Egyptian Memphis creation myth, the creation is attributed to Ptah which was not a physical but an intellectual creation by the Word and the Mind of the God. Ptah's creative thought and speech were believed to have caused the formation of Atum, the primordial God from whom all arose and Ennead a group of 9 deities including Atum. The Greeks believed that the universe was governed by an intrinsic order often described as Kosmos which was reflected in music, mathematics, and the natural world. Spoken word held an utmost importance in the Greek mythology. As seen by the myths of Orpheus, the legendary musician and poet who could charm animals and even influence gods with this powerful songs and words.

I hope you get where I am going with these examples and analogies with respect to sound and our quest to make sense of our reality and the creation of this universe. Humans are phenotypic creatures, we focus on the manifested form in the sense of what we see - more than what we hear. Audition is secondary while sight is primary. Shifting our attention to sound reveals it as the primary medium through which we have historically deciphered reality. To speak is not merely to label, but to instantiate - to execute a universe through the power of utterance. Language therefore, is not just a tool for communication it is the very architecture of the human experience.

Introduction: Phonology, the study of sound patterns in language

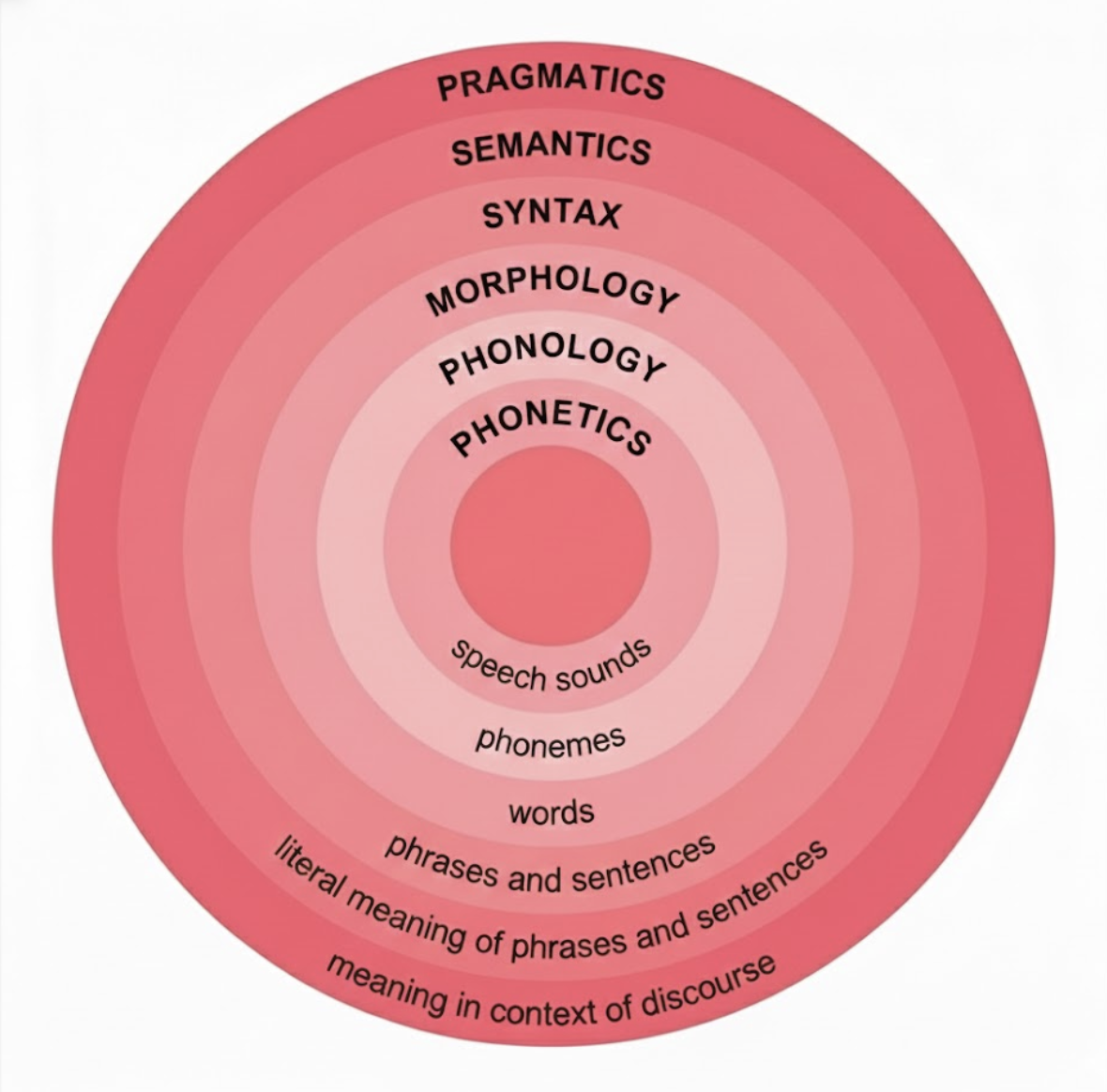

Language is a structured system of communication consisting of grammar and vocabulary. Language forms the primary means by which humans convey meaning in spoken, signed, and written forms. There are various theories around how language evolved but the truth is we do not know; all theories are just speculation. But that doesn't stop us from not studying this phenomena and trying to understand its intricacies. The study of language is called linguistics. But since language is such a complex phenomena, linguistic is not confined to study just one aspect of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (production of speech sounds), phonology (the topic of this section), and pragmatics (how the context of use contributes to meaning).

Language begins with sound, when most of us think of language we think of speaking. If there is no sound there is no language (exception being sign language). Phonology is the study of the categorical organisation of speech sounds in languages. It studies how sounds are organised in the mind and used to convey meaning. Then there's phonetics not to be confused with phonology. Phonology studies the abstract ideas of sound and how we use those sounds to communicate whereas phonetics is concerned with the physical act and properties of sound. We make variety of sounds using lips, tongue, mouth and some bits of our throat. If you want to make let's say a [b] sound, you close your lips first and then open it and release the air all at once. Phonetics deals with how we make this sound, how we hear it, how we can describe it deal with them empirically, and how we can make it visible to its practical to write it down and print.

Phonology investigates how sounds are organised in a particular language and how these sounds follow rules and a predictable pattern. These investigations are also focused on how the sounds are stored and processed in the brain and what's their function in conveying meaning in the linguistic contexts. Phonology forms an interesting part of social reality as phonological patterns - how individuals use sound patterns - can indicate a lot about them, examples being their social class, regional background, educational background, ethnicity, personal identity, etc. A subfield of phonology, called sociophonetics intersects sociolinguistics explores how variations in phonological patterns correlate with social factors.

Phonology also affects language acquisition. Babies start to tune to their native languages quite early and are quite proficient at recognising and producing phonological patterns which is crucial for the development of grammar and vocabulary. Phonology from a cognitive perspective explains the mental processes involved in speech production and perception. The words stored in the brain are not just organised by semantics but also by phonological structures and this organisation affects how we retrieve and process words. Native speakers of tonal languages like Mandarin, Cantonese, and Vietnamese are more likely to have a precise and stable form of absolute pitch perception and reproduction.

Studying phonology offers a window into our minds, language and society. It shows that sound systems are not merely abstract entities but deeply connected to our social identities, cognitive processes, and our inquiries into the human mind.

Phonemes

Phoneme is the fundamental unit in phonology. A phoneme is a smallest unit of sound that can change the meaning of a word. In English for example, the sounds /b/ and /m/ are distinct phonemes because they distinguish meanings of the words like "bat" and "mat". Phonemes are abstract unit of sounds and represent a group of related sounds that speakers of a language perceive as identical. There are slight variations in how those sounds in a group are pronounced based on context and these variations are called allophones. For example the sound [p] in words "pot" and "spot". When you say pot you leave some air out of your mouth (called aspiration) after making the [p] sound but when saying spot there's no aspiration.

Note: You'll see me using two notations to describe phonemes. The notation /p/ is the phoneme as it exists in the brain as a category. The notation [p] is the phone the actual physical sound coming out of our mouths. Even though they are same phonemes /p/ there are two different phones [p] (without an aspiration) and [ph] (with an aspiration). Do not pronounce these sounds as alphabets like Pee or Bee but more like Pa or Ba.

Now that we have covered some basics of phonology, let's understand what are the sounds we need to make in order to speak a language like Sanskrit.

Indo-European: The mother tongue of Sanskrit

We all carry the past around with us all the time. We have inherited our physical features - eyes, face, lips, hair, and nose - alongside deeper biological predispositions from food sensitivities and allergies to our neurological response to fear and anxiety. In genetics, these are our heritable traits; we are the living manifestation of our ancestors' biological history. It's a physical blueprint passed down from people we've never met. I hardly know anything about my great-grandparents let alone their names. If you think about it, it's quite unsettling that we do not much about our ancestors from the past who have given us so many of our traits.

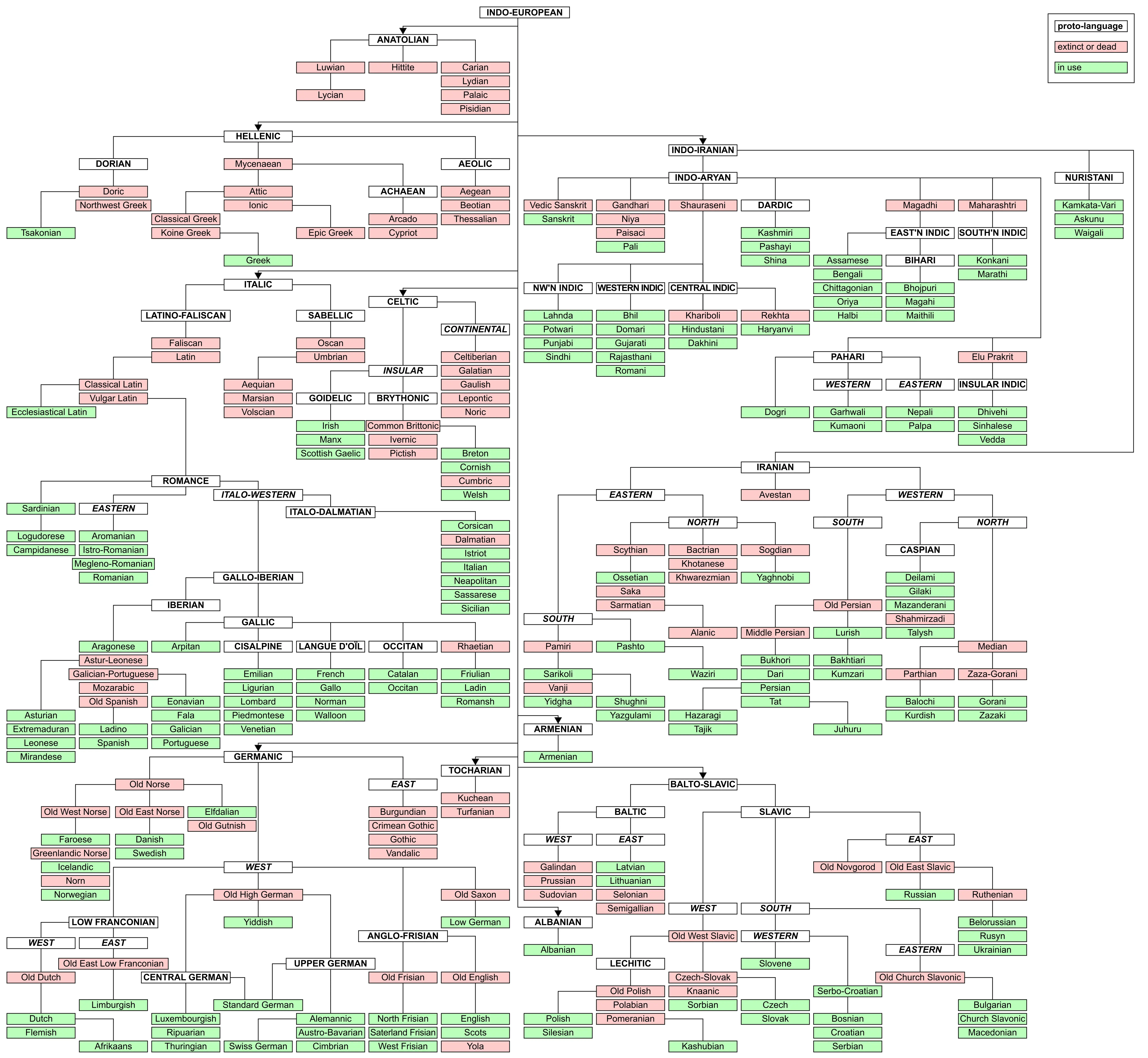

Archaeology is our best hope and way to acknowledge the humanity and importance of the people who lived before us. It is our best effort to investigate the past lives not described in writing which constitutes majority of human history. Humans have spent 95% of their time as hunter gatherers, we are biologically and phonologically calibrated for a world we no longer live in. We have absolutely no clue of how our hunter gatherer ancestors spoke and communicated. Sounds do not fossilise, we cannot know the specific vocabulary or grammar of hunter gatherers from 50,000 or 100,000 years ago. However, that does not stop us from searching for the language that our recent ancestors spoke. Many linguists believe that language we use today is the medium to know the lives of our ancient speakers. It contains fossils of of their lives and environment which we can decode. If we can reover their vocabulary through the words we use today we can get an insight into the everyday lives of the communities that lived in the past. In fact, a substantial vocabulary list has been reconstructed for one of the languages spoken about five thousand years ago and is the ancestor of modern languages like English, French, Spanish, German, Hindi, Marathi, Punjabi, Nepali, Bengali, Persian, Italian, Russian, Polish, Latvian, Irish, Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, etc. to classical languages like Latin, Avestan, and Sanskrit, ancient Greek to ancient languages like Anatolian, Tocharian. All the languages shown in the figure below descended from this same mother tongue belong to one family: Indo European language family.

Today these languages are spoken by more than 3 billion people. The origin of people who spoke this mother tongue has been a topic of fierce debate since about two hundred years now and has evolved into a cultural and racial war ever since the idea was hypothesised. From Eurocentrics to Indocentrics, nationalists and dictators have attempted to claim their country as the homeland of the people who spoke this mother tongue. So, how was this mother tongue idea materialised?

In 1771, Sir William Jones a Welsh philologist published his book Grammar of the Persian Language and was the first English guide to understanding the Persians. This book at the age of 25 earned him a reputation as one of the most respected linguists in Europe. His translations of Persian poems inspired many European Romantic philosophers. He was appointed as one of the three justices of rhe first Supreme Court of Bengal in Calcutta. He was to regulate both the English merchants and the rights and duties of Indians as the colonial subjects in the British Raj. The issue he faced soon after arriving was that although the English merchants recognised his legal authority, the Indians obeyed an already functioning and ancient system of Hindu law which was regularly cited in the court by the Hindu legal scholars called pandits. The English judges had no idea if these laws actually existed since most of the legal texts were in Sanskrit a language foreign to the judges. Jones started to read the texts and made comparisons not just with Persian and English but also Latin and Greek which he had learnt in university, with Gothic a literary form of German which he had also learnt and with Welsh his native tongue. On February 2 1786 he made the following announcement in the Asiatic Society of Bengal which he had founded when he had arrived to India:

"The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have spring from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists."

While ancient civilisations have studied grammar, the 19th century marked the birth of Comparative Philology which was the precursor to the modern linguistics. When the idea of Indo-European as a language group was introduced we only knew how to define the language family and how to determine which languages belonged to the family. The discipline of linguistics and the early analytical methods invented by the 19th century philologists are still used today to describe, classify, and explain language variations across the world. Historical linguists provided us with this ability to reconstruct parts of extinct languages for which no written evidence survives today. This is possible by relying on the regularities in the way sounds change in our mouths. Let's say if you collect the Indo-European word for hundred from the different branches of the language family and jot down the pattern of sound change in all of those words you can reconstruct a single hypothetical ancestral word as the root for that word in all of the branches. The Latin word for hundred kentum and the Sanskrit word śatam are cognates of the ancestral root word *ḱm̥tóm- (The asterisk * is a "orthographic signal" in linguistics. It tells the reader: "This word is never found in writing; it is a mathematical reconstruction"). This is a hypothetical root for the word hundred in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) mother tongue. It's a statistical average rather than a spoken word. We don't know how the word was pronounced as sounds don't leave any fossils, we can't hear the past. Linguists have reconstructed the sounds of more than 1500 Proto-Indo-European roots. So how do we know that they are accurate? Well we can't but on the other hand, archaeological excavations have revealed inscriptions in Hittite, Mycenaean, Greek, and archaic German that contained words, never seen before showing the precisely the sounds previously reconstructed by comparative linguists. This sort of gives credibility to the linguists and their reconstructed roots. Linear B was a syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek which is the earliest attested form of the Greek language. When Linear B was deciphered in 1952, it revealed a form of Greek much older than Homer. It contained a "kw" sound that linguists had reconstructed years earlier but had never actually seen in later Greek texts.

So, yes that the reconstructed roots and words are not real but at least they can be considered a close approximation and that gives a framework to work on the comparative study of the language family. The reconstructed lexicon is a window into the environment, social life, and beliefs of the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. The lexicon reconstructions show that they had words for cattle (cow, ox), otter, beaver, wolf, lynx, elk, horse, mouse, hedgehog, goose, duck, eagle, bee, honey, sheep, pig, dog, etc. The lexical evidence can be attested and compared against archaeological remains to reconstruct the environment, economy, and ecology of the speakers. So, how do linguists reconstruct such languages that we have never heard or seen in a written form?

Phonological change: How to reconstruct a dead language

Most of the languages in the Proto-Indo-European language family can be divided into 2 categories based on how the the languages represent the number 100: Centum and Satem. Centum comes from Latin and is pronounced as Kentum. Latin C is pronounced as K and this is a bit confusing for people learning Latin languages Like French and Spanish. In fact it also confuses people learning English since English uses Latin script. Satem comes from Avestan which is the holy language of Zoroastrians. Avestan and Sanskrit are daughters languages and share a lot of similarities among them. But why create such a category based on how these daughter languages represent the number 100? The answer is the sound difference. This division is based on how the Indo-European languages treat the sound coming from the back of the throat, also called as velar which is the soft palate at the back of the mouth and include phonemes like [k], [g], etc. The satem languages are the eastern division of the language family geographically speaking and include languages like Indo-Iranian, Armenian, Albanian, and Balto-Slavic. The centum languages are in the western group and include Greek, Italic, Germanic, and Celtic. These two words are cognates as they both mean "100". However, much like any other category of taxonomy we come up with there are always exceptions. Tocharian (now extinct) an Indo-European language from modern day northwest of China in Xinjiang is part of the centum family. The word for 100 in two of the dialects of the language was känt (Tocharian A) and kante (Tocharian B). So, this division is merely academic and does not actually show a clear geographic divide within the Indo-European language family.

Before we dive into how linguists reconstruct a dead language let's clear up some terminologies and concepts used in linguistic.

Stops vs Fricatives vs Affricatives

Pay attention to the highlighted sounds in these words:

- b in bat

- s in sun

- j in judge

These 3 sounds sound so different when you say the words. These sounds are the 3 most important type of sounds in human language: Stops, Fricatives, and Affricates respectively. In phonetics, consonants are classified by how the airflow is obstructed through the vocal tract which is called the manner of articulation. Articulation is how we shape or obstruct the air flow from our lungs as it leaves our body to create different sounds. If the airflow is completely blocked and then released we get a stop which is also called a plosive. If the airflow is partially obstructed creating friction we get a fricative. If you combine the two - block first, then release into friction - we get an affricate. Some examples of each in English:

- Stops: [p], [b], [t], [d], [k], [g]

- Fricatives: [f], [v], [th] or [θ], [s], [z]

- Affricates: [tʃ] 'ch' in chat, [dʒ] 'j' in judge

The character ʃ is called Esh and it represents fricative, eg. 'sh' in ship.

The character ʒ is called Ezh and is the voiced twin of Esh, meaning your vocal chords vibrate when you say the j in judge.

Voiced vs Unvoiced sounds

The air moving up from the lungs through the vocal tract must move through the larynx or the 'voice box'. Two folds of muscle and tendons, called as 'vocal cords' project inwards from the sides of the larynx. The air has to pass between these two folds. The air will vibrate if the folds are closed and it won't vibrate if the folds are open. A voiced sound is produced when the air causes the edges of the folds to touch, close, and. vibrate. This creates a sort of buzzing sensation in the throat. Whereas, an unvoiced sound is made when air flow from the lungs flows freely to the mouth where the lips, teeth, and tongue change the sound. Just put a finger over your Adam's apple while making a sound to check if the vocal cords vibrate or not to distinguish between a voiced and an unvoiced sound.

The phonemic system of IE contained vowels, semivowels, and consonants. The IE consonant system consisted mostly stops.

| Labials | Dentals | Palatals | Velars | Labiovelars |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | t | k̂ | k | kw |

| ph | th | k̂h | kh | kwh |

| b | d | ĝ | g | gw |

| bh | dh | ĝh | gh | gwh |

Table 1.1: The Indo-European Stop System, showing the five places of articulation across four voicing and aspiration states.

The Latin word for 100 is Centum (pronounced Kentum) and sometime in early Medieval French there was a dialectical version of this word which was tsent'm. The sound change that has occurred here is called palatalisation. In instances where c (k) a velar sound was preceded by a front vowel - vowels produced when the tongue is positioned towards the front of the mouth like i and e - went through a softening process and turned into a dental affricate [ts]. By the time modern French evolved the [ts] sound was simplified further and turned into a sibilant [s], so the word for 100 in French is cent (pronounced with s). This process of sounds changing into sibilants for example /s/, /z/, /j/, /ch/, /sh/, etc. is called assibilation. Latin cera [kera] 'wax' became French cire pronounced seer and Latin civitas [kivitas] 'community' became French cité pronounced seetay. These sound changes were not random and confined to certain words, they spread systematically to all similar sounds in the language. In instances where Latin k- was followed by back vowel (-o) it remained a k-. For example, Latin costa 'rib' is French côte. Even English inherited this sound system from French as we can see in words like cell, certain, central, center where the [k] has turned into a sibilant because of front vowels while words like cut, cot, cat still have the [k] sound since they have back vowels after /c/.

Human language is governed by rules and they determine the sentence construction (syntax), the relationship between sounds of words (phonology and morphology), and their meaning. The direction of sound changes are governed by two constraints: ones that are generally applicable across most of the languages, and those specific to a single language. The general constraints are imposed by the biological and mechanical limits of the human vocal anatomy. Constraints within a language are imposed by the limited range of sounds that are acceptable and meaningful for that language. Using this piece of knowledge linguistics can determined which phonetic variants came first and which ones came later. But how do they make these decisions?

Two general rules help figure out the order. One is that initial hard consonants like k and g tend to move towards soft sounds like s and sh if they change at all but a change from s to k would be quite unusual. Another one is that a consonant pronounced as a stop in the back of the mouth k is more likely to shift toward the front of the mouth t or s in a word where it is followed by a vowel that is pronounced in the front of the mouth. This phenomena is termed as assimilation: one sound tends to assimilate to a nearby sound in the same word, simplifying the movements needed to say the word. The specific type of assimilation of k to s is called palatalisation. In fact, palatalisation has been a key factor in development of French from Latin and is responsible for much of the unique phonology of the French language.

Assimilation usually changes the quality of a sound and sometimes removes sounds by combining two sounds together. The opposite of assimilation is the addition of new sounds to a word. Many native English speakers insert [-uh] when they say athlete. Instead of two syllables Ath-Leet it turns into three: Ath-uh-Leet and introduces a schwa sound uh. The schwa sound is also known as the lazy sound.

The two phenomenon explained above are called phonological and analogical changes and are the mechanisms through which new forms are incorporated in a language. Linguists examine several different points in the past - inscriptions in say classical Lati, vulgar Latin, early Medieval French, later Medieval French and modern French - to map the all the phonological and analogical shifts in the evolution of French from Latin. Let's now understand how the word for 100 was reconstructed for Proto-Indo-European.

The first thing linguists did was that they gathered up all the daughter words of the Indo-European language family in a list. Here, knowing the rules for the sound change is of utmost importance as some sounds can change radically. Let's take hundred as a reference.

| Language | Term |

|---|---|

| Welsh | cant |

| Old Irish | cēt |

| Latin | centum |

| Tocharian A | känt |

| Tocharian B | kante |

| Greek | ἑκατόν |

| Old English | hund |

| Old High German | hunt |

| Gothic | hunda |

| Old Saxon | hunderod |

| Lithuanian | šimtas |

| Latvian | simts |

| Bulgarian | sto |

| Lycian | sñta |

| Avestan | satəm |

| Old Indic | śatám |

Table 1.2: Indo-European Cognates for the Root "Hundred"

The linguists asks: are these words phonetically transformed daughters of the a single parent word? If yes, they are cognates. Also, to prove they are cognates they need to be able to reconstruct the sequence of phonemes that could have developed into all the documented daughter sounds through the known rules.

Let's look at the first word. We have 3 variations in the sounds: [k], [h], [s]. The [k] in Latin can be explained if the parent PIE term began with a [k] sound as well. But what about Avestan, Old Indic, and Lithuanian [s]. Remember hard consonant sounds tend to soften through palatalisation so if the parent PIE began with a [k] then it is quite plausible that these language groups went through a sound change and turned to a sibilant [s]. Well why can't we argue that the sound shift happened from [s] to [k] and that PIE had [s] as the first sound? Going from a sibilant fricative (s) to a velar stop (k) is rare for several physical reasons:

- Complexity: A [k] sound requires a total blockage of airflow at the back of the mouth (the velum), followed by a sudden release of air. A [s] sound is a continuous stream of air pushed through a narrow gap.

- Energy expenditure: Stops like [k] and [g] require more muscular tension in the tension and throat. We tend to naturally gravitate towards path of least resistance which is why [k] often softens into [s] or [sh].

- Articulation: Sounds usually move forward in the mouth (palatalisation). Moving a sound from front to back is unnatural for the tongue in rapid speech.

| Transition Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Hard → Soft [k → s] | PIE *ḱ → Skt ś |

| Back → Front [k → ch] | Lat C → Ital ci |

| Soft → Hard [s → k] | very rare |

Table 1.3: Directional phonetic transitions

So we can add more weightage to the possibility that [k] was the first sound in the parent PIE word but what about the [h] in Gothic, Old Saxon, Old English, etc.? These daughter languages are in the category of Germanic languages, English is a Germanic language using the Latin script. There was a consonant shift in PIE throughout the prehistoric pre-Germanic language community which gave rise to a new Proto-Germanic phonology which was retained in all of its daughter languages including English. This consonant shift was first documented by Jakob Grimm and is called Grimm's Law (also known as the First Germainc Consonant Shift). It states the following:

-

Proto-Indo-European voiceless stops change into Proto-Germanic

voiceless fricatives.

- p → f

- t → θ

- k → h

-

Proto-Indo-European voiced stops change into Proto-Germanic

voiceless stops

- b → p

- d → t

- g → k

-

Proto-Indo-European voiced aspirated stops change into

Proto-Germanic voiced stops losing their aspiration

- bh → b

- dh → d

- gh → g

The PIE [k] went through a process called spirantisation where the stop becomes a fricative so [k] turned to a [ch] sound. Think of [ch] as how you would say Bach. Then this [ch] sound underwent debuccalisation where tne point of articulation moves from the mouth to the throat which then turn [ch] into just h. Latin caput 'head' shifted to Old English hafud, Latin pater 'father' shfted to fater.

So, comparing the different daughter words and seeing a [h] sound in Germanic language might seem out of place but thankfully we have theories on why out of place sounds actually make complete sense. With this evidence we can conclude that the first letter in PIE hundred was definitively a k.

I won't go in full detail of how the linguists reconstructed the whole word as it would get too long but this small introduction should be able to provide you with a gist of the complete process. Now that we know about the phonology of PIE and how sounds change overtime to form new languages let's try to understand how this phenomena helped develop the sounds in Sanskrit.

Sanskrit phonology

Sir William Jones discovered in 1786 what Indian grammarians had known for over two millennia: that languages are systematic, that sounds follow patterns, that speech can be analyzed algorithmically. While European historical linguistics focused on reconstructing dead languages through comparison, Indian grammatical tradition took a different path achieving precision in describing the actual mechanics of living speech.

When Pāṇini (the greatest grammarian to ever live) composed his Aṣṭādhyāyī (Eight Chapters) around the 4th century BCE, he wasn't comparing Sanskrit to other languages or reconstructing its history. Instead he was creating a complete generative grammar of the language as it existed, with its phonology at the foundation. The opening verses of his work present the Śivasūtras: a compressed encoding of Sanskrit's entire sound system organized by articulatory features.

This grammatical tradition preserved not just Sanskrit's sounds but detailed knowledge of how to produce them: where the tongue goes, when the vocal cords vibrate, how air flows through the mouth and nose. It's this tradition of phonetic analysis, not comparative reconstruction that guides our exploration of Sanskrit sounds. We're not inferring how ancient speakers might have sounded but following the precise system they left us.

The speech sounds of Sanskrit are called Varṇa (वर्ण). Sanskrit is a phonetic language, unlike English which is a alphabetic language. In Sanskrit there is one to one relationship between the graphic symbol of the script and its unique phonetic symbol. Hence, each "letter" of the script corresponds to one and only one sound. An Akṣara (अक्षर) meaning 'imperishable, indestructible, immutable' is a consonant letter together with any vowel diacritics is a syllable in Sanskrit. Sanskrit itslef has no notion of phonemes, but the words like akṣar or varṇa can be used in reference to phonemes but often also with syllables. Sanskrit has always been written exaclty as its pronounced. This was important since Sanskrit was used by the priests of the Vedic tribes to sing hymns asking for blessings from their gods. Any change in the pronunciation can break the hymn and hence render your hymns useless.

In linguistics, a distinctive feature is the most basic unit of phonological structure that disinguishes one sound from another within a language. Sonority is the degree of openness of the stream of air exhaled through the lungs. A hierarchy of sonority from highest (completely open) to lowest (completely closed), creates a distinctive manner of articulation as follows:

- Vowels (स्वर): The air flow is continuous and the sound is made by the placemen t of the tongue in the mouth.

- Approximants (अन्तःस्था): Here the air flows out continuously but the tongue nearly comnes in contact with parts of mouth.

- Nasals (अनुनासिक): Most of the air streams out through the nose, the closed back part fo the oral cavity becomes a resonance chamber for the sound produced.

- Fricatives (ऊष्मान): A small confined space is created in the mouth and the air flow is swirled to create a fricative.

- Stops (स्पर्श): The tongue or the lips completely block the flow of air.

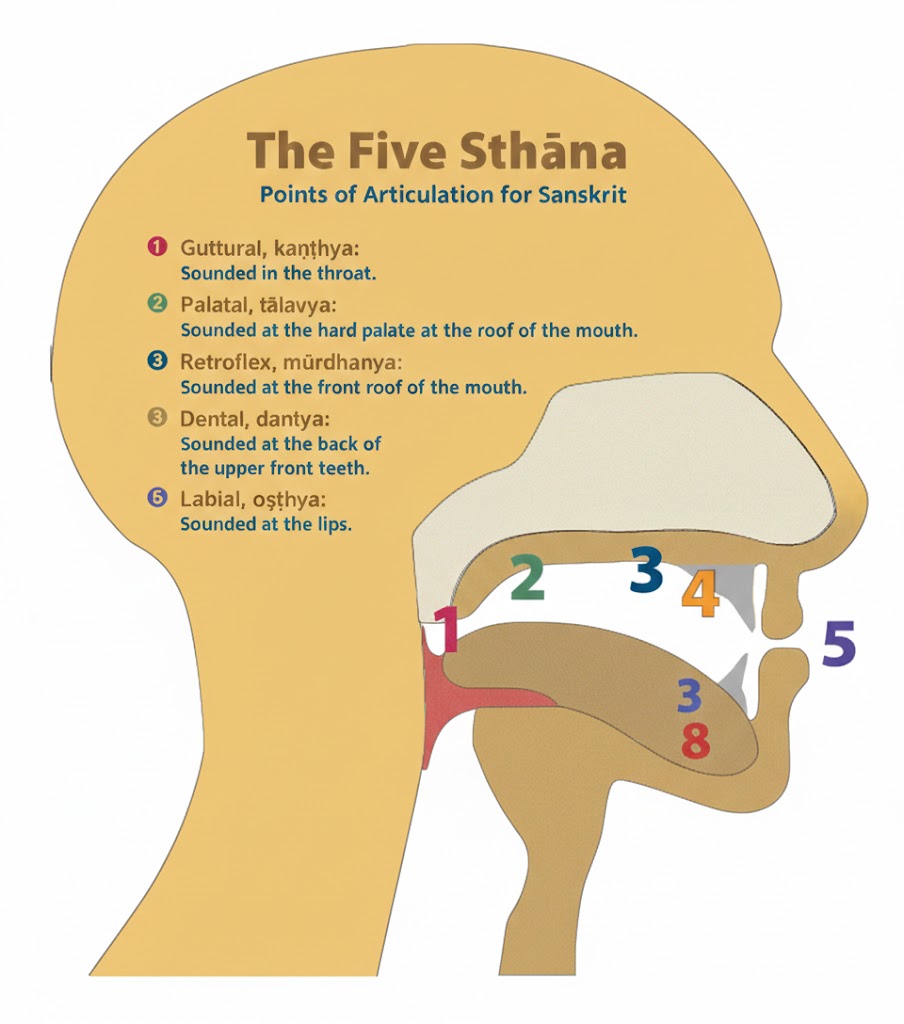

Length is the relative duration with which a phoneme is pronounced. A phoneme is either short (ह्रस्व) or long (दीर्घ). If the vocal chords vibrate when the phoneme is pronounced it is voiced (घोषवान्) else it is unvoiced (अघोष). All vowels are voiced. If a burst of air is released when a consonant is spoken it is aspirated (महाप्राण) else it is unaspirated (अल्पप्राण). The place in the vocal apparatus where the phoneme is pronounced is called the place of articulation (स्थानम्). Ancient Indian linguists whose works unfortunately haven't survived have identified the following places:

- Velum / Gutturals (कण्ठ्य): The back of the throat.

- Palatal (तालव्य): The soft palate.

- Alveolar ridge (मूर्धन): The hard palate.

- Teeth (दन्त): Behind the top front teeth.

- Lips (ओष्ठ)

The Sanskrit phonetic system consists of some 47 discrete sounds, represented by equal number of discrete symbols.

| Articulation (Sthāna) | Vowels (Svara) | Stops (Sparśa) |

Nasal (Anunāsika) |

Semivowel (Antahstha) |

Sibilant (Ūṣman) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Unv. Unasp. | Unv. Asp. | Voi. Unasp. | Voi. Asp. | ||||

| Velar (कण्ठ्य) | अ (a) | आ (ā) | क (ka) | ख (kha) | ग (ga) | घ (gha) | ङ (ṅa) | - | ह (ha) |

| Palatal (तालव्य) | इ (i) | ई (ī) | च (ca) | छ (cha) | ज (ja) | झ (jha) | ञ (ña) | य (ya) | श (śa) |

| Retroflex (मूर्धन्य) | ऋ (ṛ) | ॠ (ṝ) | ट (ṭa) | ठ (ṭha) | ड (ḍa) | ढ (ḍha) | ण (ṇa) | र (ra) | ष (ṣa) |

| Dental (दन्त्य) | लृ (ḷ) | ॡ (ḹ) (really rare) | त (ta) | थ (tha) | द (da) | ध (dha) | न (na) | ल (la) | स (sa) |

| Labial (ओष्ठ्य) | उ (u) | ऊ (ū) | प (pa) | फ (pha) | ब (ba) | भ (bha) | म (ma) | व (va) | - |

| Palato-Velar (कण्ठतालव्य) | ए (e) | ऐ (ai) | |||||||

| Labio-Velar (कण्ठोष्ठ्य) | ओ (o) | औ (au) | |||||||

One really important feature of the Sanskrit phonetic system is that its sounds are arranged on a scientific basis. With English you have to memorise all the alphabets as there is no logical organisation in the arragement of the letters, the order is historical lineage than a scientific one. The letters originally represented physical objects which Phoenicians inherited from a system that traes its root back to Semitic people in the Levant and Egypt. A - Aleph meant "ox", B - Beth meant house, and G - Gimel meant Camel. Wait G? How come G is before C? In the Greek alphabet the order was Alpha (A), Beta (B), Gamma (Γ). The Etruscans who lived in Italy adopted the Greek alphabets before Romans ever used it. The Etruscan language did not distinguish between "voiced" sounds like [g] and "unvoiced" sounds like [k] so they didn't need a separate letter for [g]. The greek Gamma was writen by some Greeks with a curved shape looking like the crescent moon C. This system was later adopted by the Romans and hence we get the alphabet letters A, B, C, so on and so forth. However, sounds in Sanskrit have been organised based on the place of articulation of the vocal apparatus starting from back of the throat velum to front of the mouth to the lips. This organisation of the sounds makes it easy to remember and articulate them. Let's look ahow each sound can be articulated.

Vowels [Svar] (स्वर)

The vowels are short [Hrasva] (ह्रस्व) or long [dīrgha] (दीर्घ). Short vowels are for one unit time [ek-mātra] (एक मात्र) "with one measure" and the long vowels are pronounced for twice as long as the short ones [dvi-mātra] (द्वि मात्र) "with two measures".

-

Velar vowels: When articulating these vowels, half open your mouth

in a relaxed way. While the short vowel is only briefly sounded,

the long ā resounds. Both these cause vibration deep down in the

throat (guttural).

- a: pronounced like the u in "but"

- ā: pronouned like the o in "mom"

cross-section of the vocal tract illustrating the articulation of velar (guttural) vowels. The pink shading highlights the resonance area and the retraction of the tongue toward the soft palate (velum) to produce deep throat vibrations. -

Palatal vowels: Open your mouth slightly wider. The shirt i is

brief whereas the long ī resounds. Both the vowels make the palate

vibrate.

- i: pronounced like the i in "bit"

- ī: pronouned like the ee in "beet"

cross-section illustrating the articulation of palatal vowels. The diagram shows the middle of the tongue arched toward the hard palate, narrowing the air passage to create the resonance required for the short i and long ī sounds. -

Retroflex vowels: Roll your tongue behind your front teeth

(retroflex). The short ṛ almost resemlbes a click of the tongue.

The long r̥̄. makes the tip of the tongue vibrate behind the front

teeth.

- ṛ: pronounced like the r in "rig"

- r̥̄: a rare sound in Sanskrit and has no English equivalent but can be pronounced like the ṛ but the sound is held twice as long

cross-section of the vocal tract showing retroflex vowel articulation. The tip of the tongue is curled back (retroflexed) toward the alveolar ridge and the hard palate to produce the ṛ and r̥̄ sounds. -

Dental vowels: To produce these, move your tongue slightly in

front of your front teeth, blow some air for short ḷ and for long

ḹ keep the pronunciation longer. The sound ऌ/ॡ is rare in

Sanskrit, effectively occurring in only one verbal root

(√कॢप् “be fitting”).

- ḷ: pronounced like the le in "little"

- ḹ: this sound does not exist

cross-section showing the articulation of dental vowels. The diagram illustrates the tip of the tongue making contact with the upper front teeth, a position required to produce the rare Sanskrit sounds ḷ and ḹ. -

Labial vowels: Round your mouth for making these sounds.

- u: pronounced like the first u in "suture"

- ū: pronounced like the oo in "pool"

cross-section illustrating the articulation of labial vowels. The diagram emphasizes the rounding of the lips, indicated by the external focal point, which is necessary to produce the short u and long ū sounds.

The set of vowels described are called simple vowels [samānākṣara] (समानाक्षर) or monophthongs and the remaining set of vowels are called compound vowels [saṃdhyakṣara] (संध्यक्षर) or diphthongs. Well why is the second set called a compund or dipthong? Because these vowels are a combination of simple vowels and are always long in duration. Let's look at how these vowles are formed.

-

e (ए): a/ā (अ/आ) + i/ī (इ/ई) = ai (अइ) -> e (ए). When these 2 simple vowels combined the result was ai (अइ) which went through a process called monopthongisation by which a dipthong becomes a monophthong and turned into e (ए). It is pronounced like the ay in "may".

-

ai (ऐ): Yes it might seem confusing but ai is in itslef a different vowel which was formed by lengthening the grade of e (ए). We'll talk more about this lengthening process in a later article but for now think of the process as adding an a (अ) sound. So ā = a + a (आ = अ + अ), e = a + i (ए = अ + इ), and so ai = a + a + i (ऐ = अ + अ + इ).

-

o (ओ): a/ā (अ/आ) + u/ū (उ + ऊ) = au (अउ) -> o (ओ). The same process of e (ए) formation applies here. This is pronounced like the o in "rote".

-

au (औ): a + (a + u) = au. The same lengthening of grade logic applies here which gives an au (औ). Think of the word "ow" in crowd to understand how to pronounce au.

Let's look at how to pronounce the various stops/plosives. For the articulation of stops built up pressure is released by a sudden release of air. The only thing changing for different types of stops is the position of the tongue. The articulation moves from back to front of the mouth.

-

Velar stops (कण्ठ्यवर्ग):

- [k] क्: The tongue closes at the soft palate. Pronounced like the k in "skate".

- [kh] ख्: More air released after the inital sound to make it aspirated. If you remeber the Grimm's Law English does not have aspirates so I can't provide a good enough word for the pronunciation. Interesting fact about the consonant kha (ख), the word means a few different things like sky, orrifice, cavity, etc. which taken from the R̥g Veda (ऋग वेद) can mean the hole through which the axel is fit in a wheel.

- [g] ग्: The articulation is same as [k] but [g] is voiced so your vocal chords need to vibrate to make this sound. Pronounced like the g in "goat".

- [gh] घ्: This is voiced and aspirated both. No English word for this sound.

-

Palatal stops (तालव्यवर्ग):

- [c] च्: The tongue closes the hard palate and the contact is released after slight pressure. Pronounced like the ch in "church".

- [ch] छ: This is the aspirated version of [c] and sadly has no English equivalent.

- [j] ज्: This is the voiced version of [c]. Pronounced like the G in "German".

- [jh] झ: This is both voiced and aspirated, and has no English equivalent.

-

Retroflex (Alveolar ridge) (मूर्धन्यवर्ग):

- [ṭ] ट्: The tip of the tongue is rolled back behind the teeth and the contact is released after slight pressure. Unfortunately, English has no retroflex sounds that match the retroflexes in Sanskrit but approximate pronunciation could tbe like the first t in "start".

- [th] ठ्: Aspirated version of [ṭ]. Sounds similar but more aspirated to how you would say the first t in "tart".

- [ḍ] ड्: This is the voiced version of [ṭ]. Sounds like the d in "dart".

- [ḍh] ढ्: Voiced and aspirated. No English equivalent.

-

Dental stops (दन्त्यवर्ग):

- [t] त्: The tip of the tongue is between or at the front teeth and the contact is released after slight pressure. Standard English does not have this dental stop sound.

- [th] थ: This is the aspirated version of [t]. Sounds like the th in "theta" or "thin" or "thought".

- [d] द्: This is the voiced version of [t] and has no English equivalent.

- [dh] ध्: Voiced and aspirated and has no English equivalent.

-

Labial stops (ओष्ठ्यवर्ग):

- [p] प्: The lips are closed and the contact is released after a slight pressure. Pronounced like the p in "spin".

- [ph] फ्: This is the aspirated version. Pronounced like the ph in "philosophy".

- [b] ब्: The voiced version. Pronounced like the b in "bin".

- [bh] भ्: Voiced and aspirated. Has no English equivalent.

Let's check out the next category: the nasals. For nasals the closure at the place of articulation is not released. All nasals are voiced.

- Velar nasal ṅa (ङ): The tongue closes the soft palate and unlike the stops, the contact is not released and the sound is nasalised. Pronounced like the n in "sing".

- Palatal nasal ña (ञ): The tongue closes the hard palate, the contact stays and the sound is nasalised. Pronounced like the n in "cinch".

- Retroflex nasal ṇa (ण): The tip of the tongue is rolled back behind the teeth, the contact stays, and the sound is nasalised. There's no English equivalent for this sound.

- Dental nasal na (न): The tip of the tongue is. between or at the teeth, the contact stays and the sound is nasalised. Pronounced like the n in "name".

- Labial nasal ma (म): TRhe lips are closed, the contact stays, and the sound is nasalised. Pronounced like the m in "mumps".

The next category of sounds is called semivowels known as Antahstha (अन्तःस्थ). The Sanskrit word for this category of sound mean "in-between" as their sonority is halfways between that of vowels and stops. In fact these sounds are formed by vowels themselves.

- Velar semivowel: No velar semivowels in Sanskrit.

- Palatal semivowel ya (य): When the front vowel i/ī (इ/ई) is followed by a/ā (अ/आ) the final sound is a ya (य). Try it out for yourself: say i and a in succession first slowly and then rapidly and you'll start to notice you naturally shift to a ya sound. Pronounced like the y in "yellow".

- Retroflex semivowel ra (र): When ṛ/ṝ is followed by a/ā (अ/आ) the final sound is a ra (र). This is also called a vocalic r. Sounds like the r in "drama".

- Dental semivowel la (ल): When ḷ/ḹ (लृ/ॡ) is followed by a/ā (अ/आ) the final sound is a la (ल). Also, called as vocalic l. Pronounced like the l in "lug".

- Labial semivowel va (व): When u/ū (उ/ऊ) is followed by a/ā (अ/आ) the final sound is a va (व). Pronounced generally with just the slightest contact between the upper teeth and the lower lip, slightly greater than that used for Engllish w (as in "wile") but less than that used for English v (as in "vile"). Unlike English, Sanskrit does not distinguish between v and w sounds.

The last category of sounds is callled sibilants [Ūṣman] (ऊष्मान). These are fricatives where air is passed through a narrow passage in the articulatory organs, resulting in a turbulent flow.

- Velar fricative (Aspirate) ha (ह): "Aspirate" is the technical term for an unvoiced velar fricative. Pronounced lke the h "hum".

- Palatal fricative śa (श): The air swirls at the palate. For this sound, the teeth should stay closed with the llips noticebly open and the tongue is relaxed right behind the teeth. The resul is a hissing sound. Pronouned like the sh in "shove".

- Retroflex fricative ṣa (ष): Here the air swirls behind the teeth. For this sound, the teeth should be open with the tongue rolled behind the teeth and the result is a soft but dark sound. Sound similar to sh in "wish".

- Dental fricative sa (स): Here, the air swirsl at the tip of the teeth. The tongue needs to be placed near the tip of the teeth. The sound is clear and hard. Pronounced like the s in "sum".

Ok, I lied! There's two more sounds left in Sanskrit that we need to understand but these sounds are not exaclty phonemes. They do not form minimal pairs with other speech sounds. These are dependent sounds, or ayogavāhā (अयोगवाहा) as they never form a syllable and in most cases occur at the end of a syllable. Unlike other consonants they do not have a place of articulation features of their own.

- Visarg (विसर्ग) (ḥ): It is written as अ: and is a voicelss fricative without a place of articulation. It is pronounced as a slight puff of air likle the English [h].

-

Anusvār (अनुस्वार) (ṁ): It is written as अं. It is a nasal sound

without a place of articulation. It can be pronounced in two

distinct ways:

- As a nasalisation of the preceding vowel when it comes before fricatives and approximants.

- As the nasal corresponding the place of articulation of a following consonant.

Some additional notes

If you look a the table that lists the phonemes of IE you'll notice two things:

Different symbols for PIE and Sanskrit palatals:

The sounds for palatals are represented with the letters [k] and [g] while Sanskrit palatals use [c] and [j]. The reason for the different symbols used for the phonemes is that PIE had palatalised velars that became palatals in Indo-Aryan but remained velars or changed differently in other branches. The example "centum" actually illustrates a major IE division:

- Satem languages (including Indo-Aryan): PIE *ḱ → c/ś (palatal)

- Centum languages (including Latin): PIE *ḱ → k (velar)

PIE notation (*ḱ, *ǵ): Represents the ancestral palatalized velars, neutral about their exact pronunciation while Sanskrit notation (c, j): Represents the actual palatal affricates that evolved in Indo-Aryan.

Missing labiovelars:

What happened to labiovelars? They underwent systematic sound changes in Sanskrit.

Delabalisation:

Sanskrit lost the lip rounding component of labiovelars. They merged with other sounds depending on the phonetic environment:

-

kw -> k

-

gw -> g

Palatalisation:

These velars then palatalised before the front vowels (i,e).

- k -> c

- g -> j

The front vowels naturally cause the tongue to be positioned forward in the mouth. When you try to pronounce a velar (back consonant) before a front vowel, the tongue anticipates the front position and the consonant shifts forward becoming a palatal.

Example 1:

PIE gwiw meaning "live"

- gw (labiovelar: velar + lip rounding) + ī (front vowel)

- Lose rounding: g + ī

- Palatalise before front vowel: j + ī

- Result: Sanskrit jīv

Example 2:

PIE gwheym meaning "snow"

-

Delabalisation:

gwh -> gh

-

Debuccalisation:

gh -> [ɦ] -> h

The velar stop loses its complete closure and becomes a voiced velar fricative [ɦ], which eventually becomes voiceless [h]. This is called debuccalization or fricativization when a stop consonant loses its oral closure and becomes a fricative or approximant.

The gh → h change was conditional: it happened in certain environments but not others.

PIE gwher -> Sanskrit ghar- meaning "heat".

PIE megh -> Sanskrit megh meaning "cloud".

Unlike Greek which kept labiovelars as distinct in some positions or Latin which sometimes preserved them as qu, Sanskrit coompletely lost labiovelars as distinct series merging into velars and palatals.

Conclusion

From the reconstructed sounds of PIE to the sounds of Sanskrit phonology, we can trace the evolution of the language. Now that we have some understanding of the speech sounds of Sanskrit, we will examine verbs next. In Sanskrit grammar verbal roots (dhātu) are considered foundational elements and we can begin learning simple communication by starting with basic verb forms.