Where is the groove? ideation: 2nd June 2025

A couple of months ago I went to this "bush techno" gig in a hidden warehouse (it was not a hidden warehouse). To my surprise, my friends and I left in 30 minutes after reaching to the venue. The music was decent but no matter how much I tried I could not move my body to it and honestly I could not explain why moving my body to it was so hard. I am not a dancer and have only recently started to go out to gigs for dancing. I am a massive techno fan because so far in my experience of listening to different sounds/music genres like techno, house, and some Latin American music are the only genres to which I could move my body to. I still listen to a lot of other "non-dancable" genres but if I am going out for a dancing I only attend house/techno events. The only thing I could say about the music in the warehouse to my friends was "It's not groovy". The whole experience made me think about groove and what exactly does it mean when someone says "the music is groovy"? Where does groove come from? Is there a way to measure groove in music? What makes something groovy and something else not so groovy? How does it differ from rhythm? Well let's dig in and see if we can find answers to these questions I have.

What is groove?

Humans have an inclination to move with music. Be it subtle foot taps and head nods or with full on dance moves we feel this urge to somehow sync to the music we are listening to. Steve Gadd one of the best known drummers in Jazz says about groove

I've found over the years that the feel overcomes everything. If you get a good groove happening, that carries it along. If it feels good, there's not a lot you have to do. You can pick and choose your spots to dynamically respond to what's going on, but you don't have to technically, constantly challenge yourself to fill in those spaces.

How should we define the term "groove"?

The word has been in the vocabulary of musicians in popular music for

a number of decades but has only recently been introduced in the

theoretical realm where it remains subjected to a variety of

interpretations. Well let's try to get some theoretical definitions

out of the way. Groove as a musical quality is an important part of

genres like Jazz, Hip Hop, modern Pop and dance music. It is an aspect

of the music that compels us to move and that this feeling is

generally regarded as pleasurable. With regard to universality to

groove in different cultures: the Brazilian word

balanço, the Japanese word

nori, and the Swedish word

svängig are terms with similar meaning to groove.

> Groove is often called the "feel of music".

> Groove can loosely be called "the feel of a rhythm".

> Groove is principally a property internal to music itself and arises

from collected effects of various forms of musical nuances especially

in regards to microtiming.

> In music theory groove refers to the rhythmic properties of pieces

of music and/or the timing relationships of actions of individuals

interacting with the music.

> From the musicians' perspective groove is commonly referred to a

pleasing state in which the creation of music becomes seemingly

effortless and they define groove as a verb instead of a noun. When

playing in a group the groove may be experienced when the interaction

between the instruments becomes seamless and the music feels right

subjectively. Or they could say that it is related to the rhythmic

feel of a piece of music, how the individual parts or layers of the

music interlock and interact with each other to create a unified

rhythmic effect.

The meaning of the word also varies depending on how the term is used

grammatically i.e. as a noun, adjective, or verb. A groove is as a

noun could refer to a repetitive pattern as well as a feeling that is

pleasing and induces body movement. To groove could mean playing

together in an effortless manner. Though the word groove has a long

history in the field of music making its occurrence in the books on

popular music theory is rare. The second edition of The New Grove

Dictionary of Jazz defines groove as "a persistently repeated

pattern". Jeff Pressing a psychologist and music researcher says

groove can be defined as a kinetic framework for reliable prediction

of events and time pattern communication. Let's understand what that

means here. Kinetic refers to the physical movement of motion. Groove

transfers energy from musicians to listeners through predictable

patterns that generate momentum. Perceptual and productive rivalries

are established against a stable framework. What are rivalries here?

It is a neurological phenomenon where competing ideas form in our

brains for a sensory stimulus. It means that while a single stimuli is

presented the perceived image or sound in this case will switch

between two distinct perceptive ideas of what the stimulus is. An

optical illusion is a good example of a visual rivalry. Ok what about

perceptual rivalries? This means we hear the music in two different

ways at once. One example is Queen's We Will Rock You song pattern:

Stomp-Stomp-CLAP, Stomp-Stomp-CLAP. Is the clap the main beat or the

stomps? So what's a productive rivalry? Also called Binocular rivalry,

in this phenomenon the brain alternates between perceiving two

different stimuli to each sensory organ even if those stimuli are not

inherently conflicting. In music this means our heads can move to one

beat but our foot or hips can move to some other beat.

Another definition comes from musicologist Richard Middleton who

summarises groove as understanding of rhythmic patterning that

underlines its role in producing the characteristic rhythmic feel of a

piece, a feel created by repeated framework within which variation can

then take place.

Ethnomusicologist Charles Keil who has gone so far to introduce a new

branch of study called "groovology" based on this theory of

"Participatory Discrepancies" or PDs. For him groove is a process

rather than a thing, a verb than a noun. Keil acknowledges the

traditional view that expressivity of music and its meaning is rooted

in its musical syntax especially in the Western art music repertoire

yet he claims that syntax does not explain the expressivity of many

other forms of music performance around the world. His idea of

expressivity of music includes substantial proportions of

improvisation (eg. Jazz) and spontaneity, music that is a process and

music that has groove i.e. music that motivates a motor response in

listeners. In his book published together with Steven Feild

Music Grooves, he says participatory

discrepancies - deviations from precise metronomic timing

relationships as a central source of groove. He says "everything has

to be a bit out of time, a little out of pitch to groove" and is

therefor the fundamentally imperfect result of a collaborative

process. These subtle timing variations can include:

- Playing slightly ahead and/or behind the beat.

- Varying the duration of notes

- Shifting accents within rhythmic patterns.

- Creating micro timing differences between instruments.

These discrepancies aren't random but meaningful expressive choices

that create tension and release. They are what makes music alive,

rhythmic, and engaging rather than mechanically precise.

Musicologist David Brackett combines a number of ideas to define

groove. First, groove is a feature of the Western African musical

tradition. Second, it is the result of a relaxed and flexible attitude

to the underlying metronomic pulse. Third, that those definitions

should suggest "too positivistic a formula". What he means by the

third point is not to take the definitions as a complete scientific

formula that fully explains a groove. Musical concepts like groove

cannot be perfectly defined through objective and scientific analysis

alone. He adds:

Discerning why some bands "groove" more than others is a complex affair. ... a groove exists because musicians know how to create one and audiences know how to respond to one. Something can only be recognised as a groove by a listener who has internalised the rhythmic syntax of a given musical idiom.

Musicologist Vijay Iyer provides a qualitative description of groove.

In groove contexts musicians display a heightened microscopic

senitivity to musical timing anf these musical quantities combine

dynamically and holistically to form what some call a musician's feel.

He says groove based music features a steady virtually isochronous

pulse that is established collectively by an interlocking composite of

rhythmic entities and is either intended for or derived from dance.

That's a very technical definition of what a groove is so let's unpack

it. He says for music to be groovy there has to be a consistent

underlying beat that listeners can predict and follow, isochronous

meaning equal time intervals between beats. The spacing has to be

virtually (almost perfectly but not mechanical) regular. NO single

instrument can create groove, it is a collective effort of various

instruments to create the pulse with each instrument contributing to

the overall rhythmic foundation. To be groovy each instrument has to

play different rhythmic patterns on the main pulse and the distinct

rhythms interlock together like puzzle pieces. Thin of it like this:

kick drum on beats 1 and 3 (strong beats), snare on beats 2 and 4

(backbeats), bass with a complex pattern using 8th or

16th notes, and hi hats on steady 8th or 16th

notes. Each sound occupies different rhythmic spaces.

The groove then gives rise to the perception of steady pulse in a

musical performance and it engages the "walk" (locomotor) channel of

the listener's sensorimotor system giving rise to entrainment.

Entrainment is when our body's internal rhythm synchronises with an

external rhythmic stimulus. So, basically when we automatically lock

in with the music because the music is so groovy.

Ok so that's a lot of theoretical definitions for groove and that is

one way to define groove. Groove as an inherent property of music and

something that exists in the music itself and is characterised by a

steady pulse, micro timing deviations, participatory discrepancies,

interlocking rhythmic patterns, etc. which we call the "feel of the

music". Music has a groove, the feeling which accompanies after

perceiving the sound of music is a by product of our apprehension of

music's groove through our bodies.

But what happens when I listen to something that has all of the

aforementioned characteristics and still not be able to move my body

to it and be able to dance to it? One account groove is the feel of

the music and on the other groove is the psychological feeling which

is induced by music of wanting to move one's body. The first account

can be termed as

"groove as feel" and the other can be

termed as "groove as movement".

Both concepts involve rhythm and body but groove as a feel is more of

a technical craft. For instance if two drummers play the exact same

beat but one hits the snare 20 millisecond behind the beat (laid-back

feel) vs exactly on time. Think of a chef using their knife skill to

perfectly cut a piece of meat - the technique of how they cut not

whether the cooked meat tastes good.

Historically groove research began in the humanities i.e. mainly in

the fields of musicology, ethnomusicology, and philosophy with a focus

on rhythmic microtiming deviations in recent years the scope has

broadened and usage of empirical methods to study groove mainly in

psychology and neuroscience. Here researchers are applying statistical

methods which enabled them to find general tendencies related to how

people experience groove. In case of groove as a movement it can be

roughly defined as the feeling generated by music that induces bodily

movement and centering the psychological inquiry on the movement

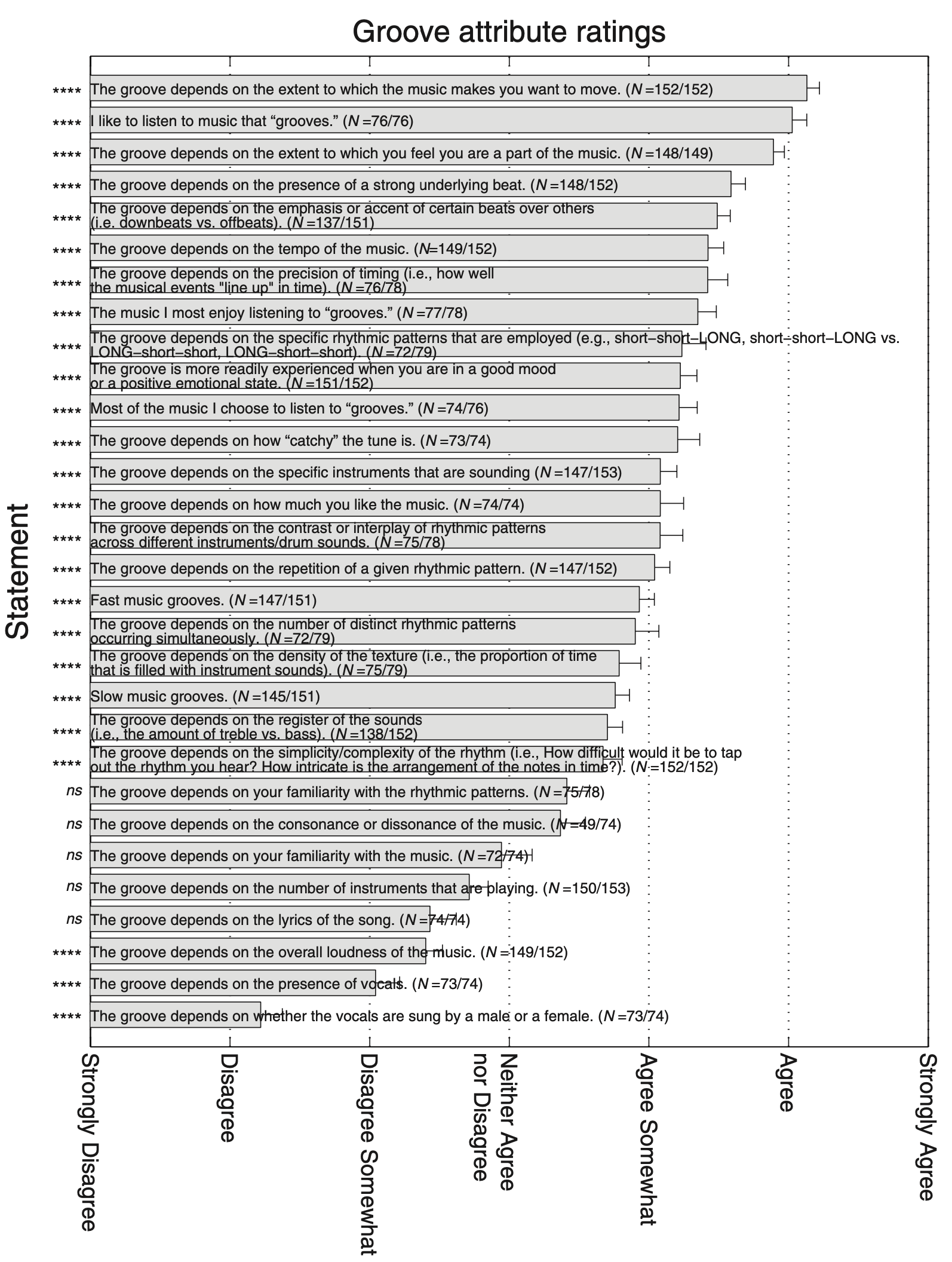

inducing feature of groove is well supported. Petr Janata a

neuroscientist, has conducted an excellent study understanding how

various characteristics of groove are perceived by listeners among

other things. The participants were asked to agree or disagree

(strongly or otherwise) with a number of claims about groove and the

claim that "groove depends on the extent to which the music makes you

want to move" is the most strongly agreed aspect of groove for the

participants. Below is the complete survey response.

There are a lot of researchers who are inquiring into the psychology of groove without committing to any set of musical features as the centre of their research. Instead they are looking for explanations on what musical nuances and features cause us to move our bodies involuntarily to a particular rhythm. The traditional research into groove was centered on what musical nuances and features define groove and this is a theory first approach. The groove definitions mentioned above had a philosophical/theoretical belief on what groove must be. Their reasoning was: groove feels human and alive while machines are quantised and rigid hence groove must come from human imperfection i.e. subtle timing variations. But groove as a movement focuses primarily on groove being a psychological phenomenon conveying that groove is the feeling within the listener not the feel within the music. This is not to say the the musical nuances are not at all needed for someone to groove with a piece of music since musical features like tempo, syncopation, pulse clarity, etc do lead to increase in the overall perceived groove which I will discuss later in the article. We can then make this assumption that:

- Groove can and is understood in multiple ways

- That the musical features associated with one concept need not be associated or form the basis of both the concepts of groove

-

Both the ideas are not mutually exclusive and a failure to

distinguish between them can lead to one of the two errors:

- That musical nuances form the basis of groove as movement

- That the research from the psychology of groove as movement disproves the musical nuance theory of groove as feel

Petr Janata in his study theorises groove as a "pleasurable drive toward action" that results from sensorimotor coupling i.e. engagement of the brain's motor action system while listening to music (more on this later) and that induces a positive affective state. Groove as a psychological phenomenon then shifts the focus on the degree to which a given rhythmic music leads to experience of wanting to move and/or some form of pleasure of enjoyment. With this approach groove can be associated with any musical style that involves such experiences regardless of cultural origin. However, if we compare genres groove for African American styles of funk, jazz, hip hop, etc. as well as West African, Afro Latin, Afro Cuban, etc. tend to receive higher ratings for dancing or pleasure than other styles of music which kind of coincides with the musical nuance (music as feel) definition of groove. Groove does not only occur within individuals but also between people shared by musicians, dancers, audiences. It draws multiple individuals into the same space and synchronises their movement which may blur boundaries between the people.

Why do we groove?

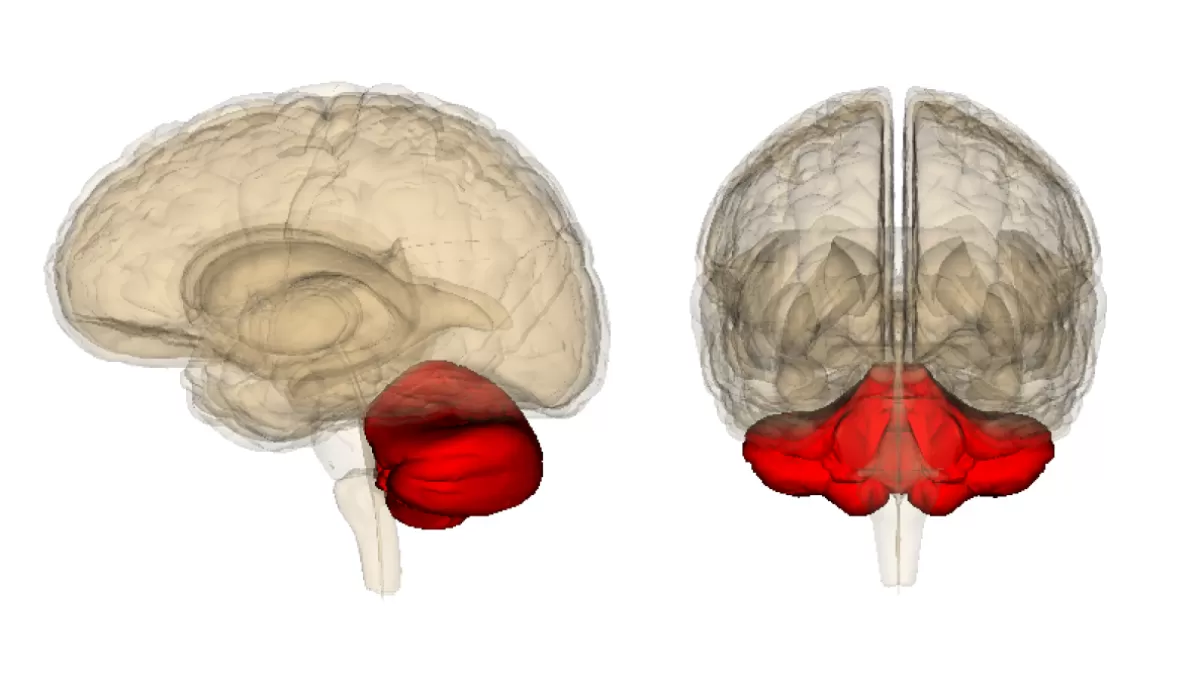

The brain is mostly for movement. We think of ourselves as rather intelligent creatures. We like to believe that our brains are capable of deep, wonderful, imaginative thoughts but reaching out to pick up a cup of tea and bringing it our mouth without spilling isn't something we boast about. Not all organisms have a brain. Plants, bacteria, jellyfish, etc do not have a brain so why do we need one? The primary need for brains is to coordinate movement. Sound, sight and other sensory information is brought together, processed and the result is used to move the muscles to achieve the goals of the organism i.e. eating and not getting eaten. Well trees do not move and they do not have brains. Yes and plants in general demonstrate that you can be incredibly complex without a brain but they just solve problems on different timescales. A tree can decide which direction to grow its branches, allocate resources between leaves and roots, prepare chemical defences, etc. but these decisions happen over days, weeks, or seasons rather than milliseconds. Imagine a predator trying to approach you and your body takes a whole season to decide to run away in the other direction. Movement creates the need for split second decisions that require centralised processing power and brains have evolved to do the same. The primary evolutionary pressure for developing brains was the need to rapidly integrate and process sensory information and coordinate motor response basically to save our lives or to drink a cup of tea without spilling it. So, coordinating much needed movements was the job of the brain and not building highly abstract models. High abstract models are conceptual frameworks that operate far away removed from our physical reality. Math, numbers, metaphysical theories, ethics, morality, quantum mechanics, linguistic... The list goes on and on. Abstract thinking piggybacks on motor systems i.e. it can be called as sort of a spandrel of motor systems. Our spine also does thinking for us sometimes. We don't always need our brains to move. Eg. touch something hot accidentally and in a split second you will snatch your hand away. Temperature sensors in the skin have quickly signalled to the spine and the local neurons in the spine have already decided to trigger the withdrawal movement for the hand. Anything beyond a reflex movement will need the brain to process the stimulus. Such reflexes are called spinal reflexes abd the brain is bypassed when such decisions need to be taken in milliseconds. When it comes to coordinating movement we have to talk about cerebellum. It is like an extra mini brain at the back.

The cerebellum is densely packed and contains 80% of all the neurons

in the brain. It is dedicated to the job of coordinating movement and

sensation. It makes sure motor movements run smoothly. Let's say you

try to reach out for that cup of tea next to you but your body is

already busy. There are muscles holding your posture, holding your

head, and keeping you balanced. When you're going to reach out for

that cup it's going to change your centre of gravity. The reach of the

arm needs to be fitted in with everything else that is your body doing

so that the overall movement of the reach is smooth and flows well

together with your body. Doing all of this takes a lot of integration

and monitoring of the sensory input and adjusting the motor system

output. Some heavy duty processing is required here that takes a lot

of neurons and the cerebellum is here to do that. Yet you only notice

when things go wrong and the cup does not reach your lips and you

spill the tea.

But now that we are creatures with highly developed brains, movement

is not the only specialty of our brains and now they have to deal with

highly abstract models living in the modern world. Living in the

modern world, you might think cognition has overtaken as primary

function of our brains but that is not necessarily true.

Cognition in a way is movement.

For example "paying attention" would be said to be a cognitive

activity but when doing that what our brains are still engaged in

movement related processes. When we pay attention to an object let's

say, the following brain regions light up:

- Sensory circuits: Process the incoming sight/auditory information

- Spatial systems: Map where everything is in relation to us

- Motor systems: Prepare the actual movements (especially eye movements)

But what about let's say paying attention in a class? It's technically not a physical object that one pays attention to if they are sitting in a class paying attention to what the teacher is teaching. Here's the thing what we think of attention as mental focusing power without any physical component is not what it is in the brain. We can not think of something in abstract i.e. to pay attention to anything our brain has to prepare our body to interact with it physically. Even when we are paying attention to an abstract idea in a lecture our brain is still

- Planning eye movements to track the location of the lecturer, or the board, or the notes

- Preparing head orientation to face the source of the information

- Positioning the body to optimise hearing and seeing

When we walk through a problem we are literally using the same neural circuits that would navigate us through a physical space. When we "grasp" a concept we are using circuits that evolved to grasp objects. So has cognition or building highly abstract models in the brain overtaken movement? Not really, cognition is movement that does not move the body. The brain is still planning the same movements but with the "execute" button turned off. The brain's primary function remains the same: plan and execute the right action but it's just that now most of our important actions are thoughts. Which leads us to a crucial revelation about our intelligence: intelligence is distributed throughout the body not just in the brain.

Much has been said about the role of the body in cognition. Recent development in cognitive science move toward the inclusion of the body in our understanding of the mind. Cognitive scientists have begun to make connections between the mental processes and physical embodiment. This new research is called embodied cognition and treats cognition as an activity that is structured by the body in an environment as embodied action. Cognition depends on experiences based in having a body with sensorimotor capabilities. Sensory processes i.e. perception and motor processes i.e. action have evolved together and are fundamentally inseparable. The traditional view of perception says: it is a passive process where your brain receives sensory input, processes the information to create an internal model or representation of the world, and then decides wat actions to take based on the internal model. But embodied cognition view says: perception isn't just passive reception of sensory information but is fundamentally about guiding our actions in the world. It is an active ongoing process that directly guides your actions and your actions in turn shape what you perceive. Having a body fundamentally shapes how we think. As per embodied cognition view the mind is no longer seen as passively reflective of the outside world but rather as an active constructor of its own reality. Such behaviour is facilitated through a feedback mechanism among sensory and motor systems. The temporal information from the sensory stimuli is matched to the motor image of the body. Our brain has an internal model of how our body moves through time. The emergent neural connections between the senses and the motor system form the basis for cognition. Neuroscience supports this view. If we look at our nervous system as a system that produces motor output we can make more sense of embodied cognition. Cerebellum contains ~80% of all the neurons in the brain but constitutes only ~10% of the brain. It is connected almost directly to all the areas of the brain - sensory transmission, reticular (attention/arousal) system, hippocampus (memory), limbic system (emotions, behaviour). The "mind" thus becomes a distributed entity rather than just something residing in the brain. Cognition is seen as distributed over mind, body, activity and cultural context. We rely upon various attributes of our world, social, and cultural environment to support our mental capacities. Jean Lave an anthropologies conducted a study to see how adults of various backgrounds used arithmetic while grocery shopping. Her results showed that in making purchase decisions the subjects employed a flexible real time arithmetic in order to select better prices per unit weight, taking into account the constraints imposed by the layout of the stores, the capacities of their refrigerators, and the dietary requirements of their family members. Such use of arithmetic was rarely reflected in subjects' performance on grade school math problems. Cognition as demonstrated in practice was found to differ from cognition in abstract settings. When a bird drops a nut from a great height to crack it open does the ground become a tool? Rather the bird is exploiting an aspect of its environment to extend its physical capabilities. Hence the mind may be viewed as symbiotically embedded not within its body but also in that body's environment and structured by its surroundings. This embodied view of cognitive science allows for direct cultural interaction which is crucial for both language and music.

One might say musical groove is as something that induces motion. Our capacity to entrain (lock in) to a regular rhythm may have been an evolutionary leftover from some previously useful survival function. There are several compelling theories for this. Entrainment is defined by a temporal locking process in which one's motion or signal frequency entrains with the frequency of another system. Groups that could move in sync were more effective in hunting, gathering and defending. Being able to predict regular temporal patterns help with anticipating animal movements during hunting. It also improves fine motor control and coordination. Research has shown that the rhythmic component of an auditory image i.e. a mental representation of sound that you can "hear" in your mind cannot be activated without recruiting neural systems known to be involved in motor activity especially those involved in the planning of the motor sequences. Our brain is constantly trying to predict what will happen next. For rhythmic patterns the best way to predict timing is to internally simulate the actions that would produce those patterns. When you observe or hear actions, mirror neurons fire as if you were performing those actions yourself. Music hijacks this ancient prediction system built into our minds which is why it feels so physical even you're just listening. When we hear or see patterns that have a specific timing and spatial arrangement eg. rhythm of music, these sensory patterns align with how our bodies naturally move. Our motor systems have a certain natural rhythm and preferred patterns of movement. Because of the sensory stimuli the brain invokes its internal model i.e. a mental image of the movement which corresponds to the synergetic elements of the muscoskeletal system even if the muscoskeletal system itself does not move. Neurons do not control each muscle individually, they instead control a group of muscles called synergies. When the sensory stimuli aligns with our body's natural rhythm and match the synergies the whole neuron pattern activates internally. The brain has mechanisms that can suppress motor output while allowing motor planning and simulation to occur which allows us to think about the actions without performing them. The muscles may show subtle activation which can be detected via electroencephalogram (EEG) but not enough to create an observable motion. This simulation stays in the brain rather than being fully executed. Remember from the previous section: cognition is movement that does not move the body, the brain is still planning the same movements but with the "execute" button turned off. Motor neurons have activation thresholds. When sensory inout matches motor patterns it activates these neurons below the threshold needed for actual movement creating "subthreshold" motor activation i.e. real neuron activity without visible physical output. A perceived rhythm is literally an imagined movement. The act of listening to rhythmic music involves the same mental processes that generate bodily motion. For example, certain musical characteristics might evoke the dynamic movement of the gradual increase/decrease in volume and intensity that naturally occur when breathing. Air flows in during inhalation which increases the volume gradually expanding our chests fully. Air flows our during exhalation which reduces the volume and our chests contract. Orchestral crescendo (gradually getting louder) and diminuendo (gradually getting softer) can evoke the natural rhythm of breathing. Musical rhythms can also evoke the steady pulse associated with walking and rapid rhythms associated with speech. These bodily movements have their own frequency. Breathing falls in the range of 0.1Hz to 1Hz, steady pulse associated with walking falls in the range of 1Hz to 3Hz, and speech falls in the range of 3Hz to 10Hz.

| Body Motion | Musical Correlate | Approximate Frequency Range (Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| Breathing, moderate arm gesture, body sway | Musical phrase | 0.1-1 |

| Heartbeat, sucking, chewing, walking, sexual intercourse, head nod | Musical pulse also called tactus | 1-3 |

| Speech/lingual motion, hand gesture, digital motion | Musically relevant smallest subdivision of musical pulse, fast notated rhythms | 3-10 |

| Phoneme (smallest unit of sound in a language), rapid flam between fingers and limbs | Grace notes, deviations, asynchronies, microtiming | 10-60 |

As shown in the table various musical characteristics resonate to our

natural bodily movements. Musical activity on these timescales exploit

the corresponding body activity. Most of the wind instrument phrase

lengths are naturally constrained by the lung capacity; blues

guitarists, jazz pianists, and

quinto players in Afro-Cuban

rumba are said to "speak" with their hands

and fingers. Such instances involve the embodiment of the musical

performer and the listening audience.

Music isn't just abstract sound patterns, it directly connects to the

natural rhythms and movements of our bodies. Our cognitive system

operates on multiple temporal scales simultaneously. Our brains are

processing different stimuli at different speeds. For example, we are

simultaneously tracking:

- Slow changes: The overall emotional feel of the conversation

- Medium changes: Rhythm of speech

- Fast changes: The individual phonemes

Music exploits this natural cognitive architecture. Our brains are

constantly solving this problem of integrating the information coming

to it at different speeds. Music provides a clear window into how this

works because music is a temporal organisation of information which

our embodied systems can latch on to. When we hear music our motor

systems do not just respond they actively predict what comes next

based on the bodily patterns it recognises. THis is why we can

anticipate musical beats and why disruptions feel surprising. Our

motor system is actively predicting where the music is going by

feeling its temporal nature and running simulations in the brain. Each

of the frequencies mentioned in the table above represent different

possibilities for actions that our bodies naturally support. Our

bodies have natural resonant frequencies determined by the things like

limb length, muscle fibre type, neural processing speeds, etc. Music

that aligns with these constraints feels "right". Different sensory

and motor systems (breathing, walking, speaking) operate as integrated

units. Music succeeds by activating different systems at the same time

creating a rich, layered embodied experience.

When musical rhythms match bodily rhythms, the natural oscillations in

the brain synchronises to the rhythms creating coherent patterns of

activity. This is why music can feel so compelling and why it affects

mood and attention. Prediction and successful prediction leads to

rewards in the brain. Music that successfully activates multiple

bodily systems at once creates a rich satisfying experience. If it's

too simple then things get boring, if it's too complex then our bodies

can not follow it. Understanding music isn't just happening in the

auditory cortex, it involves motor, respiratory, speech, and dynamics

of breathing itself. While musical styles vary culturally the

underlying frequency ranges suggest universal constraints based on

shared human embodiment.

What makes it groovy?

Pulse: The presence of groove is music depends first and foremost on a strict pulse. A pulse is the steady "beat" that you feel throughout a piece of music like a musical heartbeat. These are regular recurring beats that create the foundation of the rhythm. The pulse may be audible or implied. Like a tick of a metronome or a watch the pulse forms the basis of the temporal structure of the piece. Once a pulse has been established the listener can still follow it if the sounds in the piece have stopped. Without a fundamental reference structure such as a steady pulse to guide a dancer's feet and musician's fingers there is probably no experience of a perceived rhythm or groove. Groove based music puts a great emphasis on avoiding tempo changes which are considered destructive to a good sense of groove. It has been theorised that humans posses internal biological oscillators that can synchronise with external rhythms that are present in the environment. Biological oscillators also known as endogenous oscillators, refer to the internal biological systems that generate rhythmic or periodic activities. Such oscillators are needed to maintain various physiological processes such as circadian rhythms, heart rate, and respiratory rate. These oscillators are present in all living organisms in some form or another. These oscillators are set into motion when exposed to external rhythms and generate self sustaining periodic activity that tunes into and synchronises with the pulse via a process called abstraction. These self sustaining oscillators are able to regularly adapt their period and phase to the changes in the external rhythms and hence are capable of dynamic entrainment rather than just simple synchronisation. Our brain makes this timing window called beat bin. When we hear music our brains do not expect every sound to hit at the exact same millisecond, instead it has a beat bin. It is a small time window where sounds can still feel on the beat. It's like a basket around each beat and the sounds that land inside the basket feel on time and sounds that do not feel off time. Computer generated music where every instrument hits exactly at the same moment creates a narrow beat bin which can feel robotic. A live band where bass hits slightly before the drums and maybe guitar slightly after creates a wide beat bin to include all these sounds. Everything still feels on the beat but this has more richness to it and does not feel robotic. When instruments are slightly off sync our brains do not think this sounds bad. Instead, it adjusts its expectation and makes the timing window bigger so that all of the instruments can fit inside and still feel groovy.

Meter: Now that we

have an established pulse in the piece of the music which is pretty

much identical, if we were to accentuate some pulses and others not we

create a small group of such accentuated pulses. Any regular pulse

train consisting of identical equally spaced elements will posses no

inherent rhythm or groove. There must be a slower pulse train on top

of the main pulse train and it must be a multiple of the main pulse

train eg. every two, three, four, etc. For example if we take 2 pulses

in the pulse group and accentuate first pulse, we'll end up with this

pattern of accentuation: Strong-weak.

Or we could take 3 pulses, accentuate the first one to get a pattern:

Strong-weak-weak. In fact we have a

tendency to group pulses in such smaller groups to easily identify and

process the overall piece of the music. Such repetitive, regularly

accentuated pulse group is called meter. Meter logically requires two

levels of motion. Without the main faster oulse train the slower pulse

train (meter) is merely a set of regular recurring elements and

similarly without the slower pulse the faster pulse is merely a set of

regular recurring elements. When we walk we might go

LEFT-right-LEFT-right-LEFT-right. Some

steps feel stronger when you push off and some steps feel weaker when

you just land and this creates a pattern that repeats. Musical meter

works the same way. Meter can be classified by counting the number of

beats from one strong beat to the next. For example if the music feels

like "strong-weak-strong-weak", it is duplemeter. A

"strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak" is triple meter and

"strong-weak-weak-weak" is a quadruple meter. Most popular music

follow a 4/4 meter which is "strong-weak-medium-weak,

strong-weak-medium-weak". A 4/4 time signature is a bar of 4 beats and

each beat being a one quarter the speed of the main pulse. A 4/4 time

signature is the most common time signature in majority western

popular music. Meter is analogous to a time signature in music but

time signature is much more than meter, a meter is just a part of the

time signature. Inter-onset interval a fancy term for the time between

beats in music can be said to occur at various time spans ranging from

100 milliseconds to 6 seconds. The lower and upper inter-onset

interval thresholds for events in a meter of 250 milliseconds (about

240BPM) and 2 (about 30BPM) seconds respectively are strongly

associated with the human sensorimotor systems. This range in music

corresponds to a comfortable rate to which we can easily synchronise

via body movements such as foot taps or hand claps. Popular music has

a 500 millisecond interval which is about 120BPM which is quite close

to our walking pace of ~600 milliseconds between steps (100BPM).

Interval under 250 milliseconds feels too fast and frantic and is hard

to follow with body movements. Interval above 2 seconds lose the sense

of a pulse and feels like trying to march to a grandfather clock. In

groove based music rhythmic expressions occur at an extremely fine

timescale, rapid enough to rule out auditory feedback mechanism for

how the rhythmic expression is perceived. The question is how to

explain our assimilation and production of very fast sequences of

events in time given that human reflexes and neural transmission

speeds are too slow to account for them. Think of the mistakes you

make while typing fast. Your brain pre-plans the entire sequence

rather than controlling each letter individually. Our brains group

small actions into bigger units i.e. hierarchial organisation chunking

fast actions into organised patterns. In groove based music rhythmic

expressions involve micro timing deviations that occur in millisecond

ranges lie subtle rushes, drags, swings, etc. that create the feel of

music. These variations are often 10015 milliseconds in duration which

is faster than what conscious perception can track. Auditory feedback

mechanism requires time for:

-> sound production

-> sound transmission to the ear

-> neural processing of auditory information

-> motor system adjustment

-> implementation of corrective action

This entire cycle takes 100-200ms, far too slow to control micro

timing deviations that create groove so how do musicians create the

groove? In most motor activities the auditory feedback serves as

quality control system

-> monitoring output: "did i hit the right note?"

-> timing adjustment: "am i too slow or fast for the beat?"

-> volume control: "am i too loud or too soft?"

-> pitch correction: "am in tune?"

The traditional motor control theory suggests the cycle:

-> plan an action (decide to play a note)

-> execute the action (muscles move)

-> monitor the result (hear what actually happened)

-> compare the intent (was it what i wanted?)

-> adjust the next action (correct if any errors)

This works well for gross motor control and conscious adjustments but

breaks down at fine timescales. At micro timing level (10-50ms) the

groove variations happen faster than the feedback loop operates. By

the time you could hear and correct a 20ms timing deviation multiple

beats have already passed. So, instead of reactive feedback musicians

use feed-forward control:

-> the brain creates models i.e. neural representations that predict

the sensory consequences of motor actions

-> brain sends a signal to the muscles and keeps a copy of the motor

command

-> brain predicts what should happen based on the command

-> sensory systems report what actually happened

-> brain compares predicted vs actual outcome

-> the forward model is adjusted to reduce future prediction errors

-> actions are based on this model and not reaction

Through practice timing patterns become muscle memory. At the macro

level the auditory feedback helps you stay with the overall beat &

adjust major timing errors. At the micro level the subtle timing

variations that create the feel of music must come from embodied

predictive processes. Musicians must simultaneously:

-> let go of conscious control to allow micro variations

-> still maintain overall timing through the broader auditory feedback

Syncopation: Having a bar of 4 beats

gives a special characteristic to the bar on how we perceive the

sound. The first beat is called the

downbeat and it is the most strongest beat

of all the beats. Beat 3 is the next strongest beat but not as strong

as the first downbeat. Beat 2 and 4 are called weak beats and are also

called off-beats or

backbeats. Additionally, beat 2 and 4 are

also called upbeats since they prepare the

listener for the subsequent downbeat.

Ok so now we have a steady pulse and we have grouped some pulses into

beats of 4 and created a meter. But that does not necessarily make the

piece of music groovy. Let me demonstrate with some sounds.

Listen to the audio above, there's not much going in the sense of groove. We have a kick on every downbeat and a clap on every backbeat. A backbeat is when you emphasise beats 2 and 4 in a 4/4 bar. This is a classic house/techno boom-tis-boom-tis rhythm. Listen to the audio for a while on repeat and soon you loose all your interest because it gets mechanical and does not really offer much in terms of giving you that feel to move your body. So let's try to make the rhythm a bit more groovy.

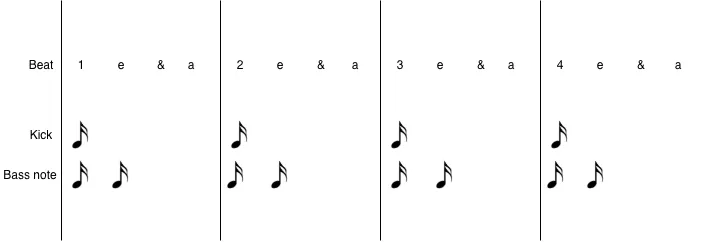

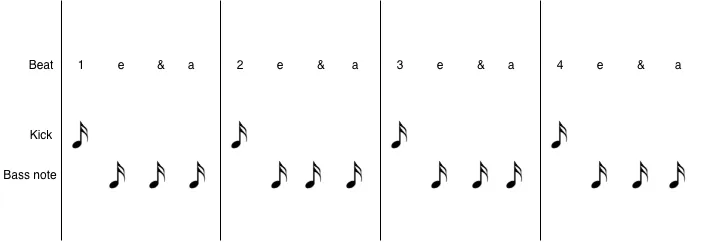

Now I have added 2 bass notes in the rhythm. One of the notes coincides with the kick and the second note is played just after the kick. The whole piece still does not feel rhythmically rich. Since one of the notes falls on the beat with the kick the emphasis is lost since the kick is already emphasising that beat and the bass note just messes up the kick sound because of frequency masking. Due to frequency masking the kick and the bass frequencies are mashing up together as they fall on the same beat and hence it gets tricky to discern the kick and the bass sound. I have also provided what a visual representation of the kick and the bass note and their relationship to the beat in the bar.

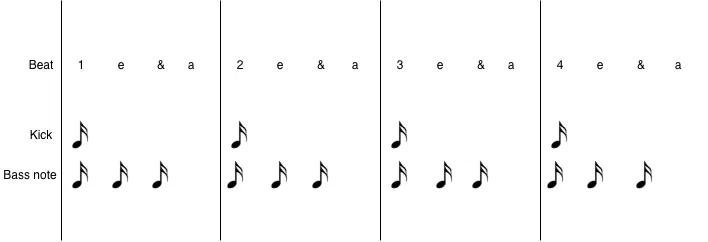

What I have done now is added another bass note so now in total we have 3 bass notes out of which one coincides with the kick and the rest two fall between the kicks. Adding the third notes starts to create a good rhythm but the groove is still missing. Also, the bass note coinciding with the kick is not really helping us. So let's do one thing. Let's move the onsets of the bass note and shift them one beat away from the kick.

The shift happens after 10 seconds and notice how the groove just starts to evolve once the bass notes are shifted and played between the kicks. This feels groovy but the rhythms is still pretty straight. All the bass notes are identical in sound and velocity as there is no emphasis on any of the bass note to accentuate the rhythm. So let's try something new to add some accentuation on the bass notes.

What I am doing now is opening the filter on selected bass notes to accentuate them. This emphasizes some of the bass notes and brings them forward in the rhythm. The amount of filter I open on each bass note creates an additional rhythmic layer that conflicts with the underlying bass pattern. Listen again as I increase and decrease the filter intensity and change which bass notes have the filter applied. This is called a syncopated rhythm. Syncopation is a technique where we emphasise the weak beats of the bar instead of the strong beats which (in case of most electronic music) has other musical events already emphasising the beat. This surprises the brain since it expects musical events to land on strong beats but emphasising the weak beats creates a rhythmic complexity fighting the main pulse and adds to the groove of the piece.

The main pulse of the music, the constant beat does not exist independently outside of the given piece of music. It is produced by the music itself. It only exists because certain events or notes of the music make it happen. Any event happening on off beats threatens the existence of the main pulse. Hence, syncopation requires both events i.e. on beat which keeps the pulse alive and off beat which contradicts it. A key factor in the experience of groove of a rhythmic pattern is the extent to which the rhythm challenges our perception of meter; syncopation violates that metric expectation. Listen to the above audio. I started with one off beat event and created a new rhythm out of it which complements the regular 4/4 metric bar of the piece.

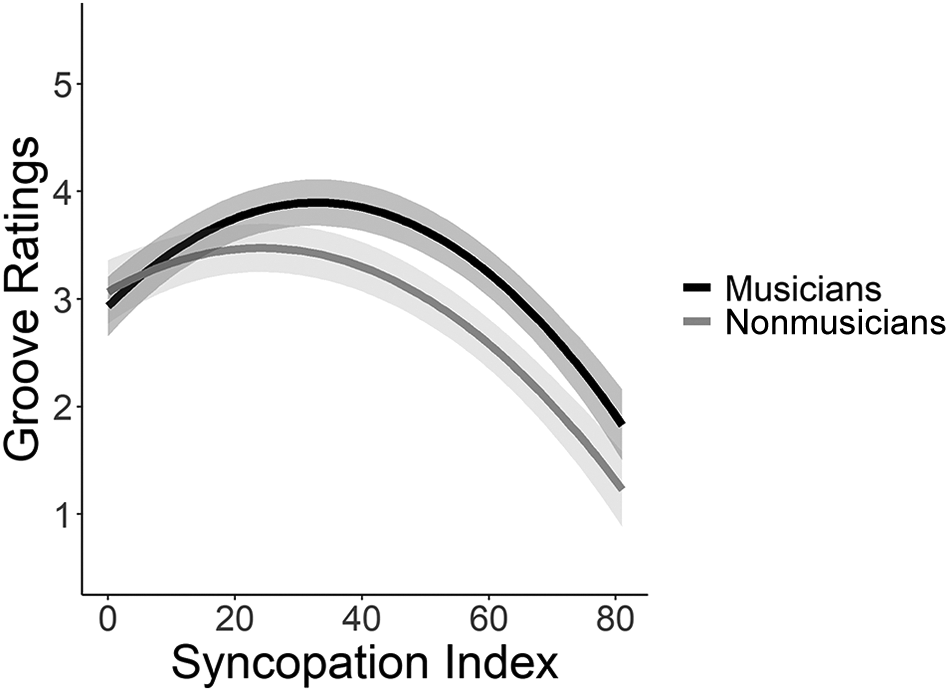

Too much syncopation does not necessarily make a piece of music more groovy instead a moderate amount of syncopation leads to higher rating of the perceived groove. There have been several studies which confirm this phenomena that when syncopation increases to a point where the rhythm is really complex the overall perceived groove reduces for the piece of music. In one of the studies on syncopation it was observed that the participants' number and magnitude of tapping errors correlated linearly with the degree of syncopation. Furthermore, as the degree of syncopation increased the participants reset their metrical perception to the syncopated rhythm and the syncopated rhythm becomes the new meter thus leaving the actual meter of the piece of music. The syncopated beats become the new "on beat" events and the listener's focus moves to this rhythm as the primary meter.

So this is how syncopation works to make a piece of sound groovy but is syncopation the only way to make something groovy? Well, no.

Polyrhythm

...but we delight in rhythm because it contains a familiar and ordered number and moves in a regular manner; for ordered movement is naturally more akin to us than disordered, and is therefore more in accordance with nature.

- Aristotle (citation needed)

Before polyrhythms let's understand basics of rhythm first.

Rhythm comes from the Greek word

rhythmos which has multiple meanings in

ancient Greek including "measure, proportion or symmetry of parts". In

the present context its meaning can be applied to the proportional

relationship of time and durations. The Greeks experienced this

temporal proportion mostly through the long and short syllables of the

Greek language as these features were used in poems and then later on

in the tones of melodies and the bodily movements of dance. The word

arithmos i.e. number implies a different

claim to rhythmos namely that rhythm

consists of discrete quantity of units which can be intrinsically

quantised. Thus this idea of unit of

measure tells us about the regularity and recurrence of a single

consistent time span. It was Aristoxenus a pupil of Aristotle who

gives us the earliest theoretical account of rhythm in terms of

proportional durational relations as the ratio between the durations

of the upward and the downward motion of the metrical verse foot

measured in multiples of a temporal unit he calls the

prôtos chronos i.e the primary duration.

The foot is the basic repeating rhythmic unit that forms part of a

line of verse in most Indo-European traditions of poetry. It is a

combination of two or more short or long syllables in a specific order

but for a Germanic language like English it is not a reliable way of

measurement and hence is also defined as a combination of one stressed

and one or two unstresses syllables in specific order. This primary

duration is the shortest duration humans can perceive and distinguish

as a separate unit. He said rhythm occurs when the rhythmised material

i.e speech in poetry, tones in music, and movements in dance is

divided into parts that are "knowable" and so produce special kind of

determinate arrangement of temporal durations that qualifies as

rhythmic. This requires the upward and the downward motion to be

mutually measurable on the same scale and that each of them be an

integral multiple of the

protos chronos which is their common

measure. Some common Greek feet: (notation: – = stressed/long

syllable, ◡ = unstressed/short syllable)

- Iamb (or iambus or jambus) [◡ ‒]: short-long (like "be-FORE")

- Trochee [‒ ◡]: long-short (like "THUN-der")

- Dactyl [‒ ◡ ◡]: long-short-short (like "CARE-ful-ly")

- Anapest [◡ ◡ ‒]: short-short-long (like "un-der-STAND")

Aristoxenus analysed these feet in terms of up and down motion:

- Arsis: rhythmically strong or accented part

- Basis: rhythmically weak or unaccented part

He was measuring the proportional relationship between the "up-beat"

and the "down-beat" portions of each foot using his

protos chronos as the measuring stick. So

a Dactyl might have a 2:1 ratio (long syllable = 2 units, short

syllable = 1 unit) and he would analyse how the arsis and basis

portion of that pattern relate proportionally to each other. Such a

foot where the upward and downward motion are integrals of the common

measure was termed as a rational foot and irrationality occurs when

such a relationship is not formed. He was not concerned with the

"mathematical" irrationality of the relationship but rather a

perceptual one. Only rhythmic pattern built from clearly perceptible,

countable units can genuinely create rhythmic experience. If the

proportional relationships are too subtle to perceive, they cease to

be "rhythmic" in any sense.

Our brains can only experience such phenomenon only if a flowing

temporal experience organises itself into discrete, countable,

perceptually clear units - θμός i.e. the

Greek deverbal suffix thmos in both words captures the transformation

from continuous activity to a structured measurable phenomenon.

In modern music theory, rhythm is the pattern of a particular sound,

silence, and emphasis in a piece of music. It is the arrangement of

notes of different lengths and it refers to the structure of notes and

rests (silence) in time and when the series of notes and silence start

to repeat themselves it forms a rhythmic pattern. Along with the

rhythm indicating when the notes are played it also specifies how long

the note is played and with what intensity. In short it is the

comparative length of notes to each other in a sequence. Rhythm is

music's central organising structure and in a way the temporal flow of

music is primarily a matter of rhythm. Oxford dictionary has 645

various definitions for the word "run". So how do you define it? With

your feet? nose? Rhythm suffers from the same problem, it means a lot

of things and they are not always clearly distinguished even in

academic discussions. What I have talked here about rhythm is just one

aspect of its definition and meaning. German musicologist Curt Sachs

asks the question "What is rhythm?" and replies: "The answer I am

afraid is so far just -- one word: a word without a generally accepted

meaning. Everybody believes himself entitled to usurp it for an

arbitrary definition of his own. The confusion is terrifying indeed."

There is no simple answer to this question. I for one really like this

definition of rhythm given by composer Jason Martineau where he states

that "Rhythm is the component of music that punctuates time, carrying

us from one beat to the next, and it subdivides into simple ratios."

Now that we know what a rhythm is we can define what polyrhythm is. Poly prefix comes from ancient Greek word meaning many so polyrhythm can be defined as "of many rhythms" but by this definition any piece of music is a polyrhythm since most music contains multiple rhythms. The key concept here in case of polyrhythms is that the rhythms must be contrasting rhythms played simultaneously. So a correct definition would be: polyrhythm is the simultaneous use of two or more conflicting rhythms that are not perceived as being derived from the same meter. Ok let's hear a simple example of polyrhythm. A really formal way to define polyrhythms is it consisting of at least two different beat levels (M & N) within one bar where M and N have to be relatively prime i.e. they should not have any common roots.

Listen to the audio which is a 4:3 polyrhythm. The orange rectangle represents the 3/4 rhythm marked by the clave and the blue rectangle represents the 4/4 rhythm marked by the bass drum. The 3 evenly spaced hits of the calve are stretched in the same timespan as the 4 evenly spaced bass drum kicks. If you try you can focus on your attention separately just on the kicks or the clave but when you zoom out and listen to the overall interplay of the two sounds it creates a completely new composite rhythm. Polyrhythms also have this unique feature when it comes to being processed in the brain. Research has shown that processing the polyrhythmic tension activates Brodmann Area 47 which is responsible for higher order processing of language.

Every piece of music you listen to has a pulse and the sensation of

this pulse automatically sets up the rhythmic framework in our minds.

This feel of the pulse is known as meter: a hierarchial structure of

different accentuations of evenly spaced beats that plays an important

role in the way our brains structure the music over time. Meter helps

the brain capture the rhythmic feel of the music. One of the ways

through which music conveys meaning to its listener is the

foreground/background (figure/ground) relations. This actually comes

from Gestalt psychology which is a theory of perception. This theory

was developed in 20th century Germany and the word

"Gestalt" means "form" and is interpreted as "pattern" or

"configuration". It is often explained with "The whole is other than

the sum of its parts". Our minds perceive whole meaningful

configurations rather than isolated elements. In vision for example,

the brain groups isolated elements and we perceive a whole rather than

the individual component. When reading the brain has to parse each

individual alphabet combine that with the next alphabet and eventually

form the whole word. We do not read each alphabet, our brains quickly

compute the data coming in from the visual system. This grouping is an

automatic process and happens without our conscious awareness. Looking

at a lawn we don't see the individual grass blades, we could if we

focus on the grass blades but what we perceptually see is the whole

lawn. This is what is theorised as "Gestalt Principle of Grouping".

Sounds group too. Listening to an orchestra we hear a cohesive sound

of all the instruments in the ensemble. Just like blades of grass we

can focus our attention to one group of instrument say the violin and

then we can make out the sound of that group but as a perceptual whole

we hear the complete ensemble. Another example is the "Cocktail Party

Problem" which is linked to Gestalt psychology with auditory scene

analysis. In a crowded party, many conversations are happening at the

same time, music is playing, glasses clink, yet somehow you can tune

in to your friend's voice while filtering out everything else. This is

the foreground/background theory of music too. This is explained by

the relationship between the local auditive events and the deep

structural layers inherently present in the music.

Ok, these are some high level technical jargons: local auditive events

and deep structural layers in music so let's understand them.

Using the Gestalt principles we can deconstruct music into components

and layer them vertically. Why vertically? Well that's how our brains

process stimuli, the lower levels process the basic properties of the

stimuli (eg. pitch, loudness, etc) which is then sent to the top

levels of the brain which combines that information with past memory,

emotions, etc. to make a cohesive sense of the stimuli and make us

experience it.

We can divide a piece of music into there layers:

- the bottom layer

- the middle layer

- the top layer

The bottom layer: This layer consists

of what we can describe the properties of the sound itself which are

dynamic, timbre and pitch. Dynamics are the amplitude or the loudness,

timbre is the shape of the sound wave, and pitch is the frequency.

These are the basic identities of the sound processed by the auditory

cortex. If you strip away the musical meaning from a sound this what

you are left with essentially, noise.

The middle layer: This layer consists

of the emergent properties of the music: harmony, mode, and rhythm.

Our preferences for these musical elements is shaped by culture

conditioning rather than innate biological or mathematical principles.

For instance harmony does not exist in many different cultures so for

someone from Western culture would not appreciate or feel the impact

of the emotions of let's say Arabic or Indian music. Mode relates to

which notes or scales are used and how they function relative to each

other. [need more info on this but would extend the article]

The top layer: This layer consists of

the musical experience that we perceive from the music: beat, tempo,

melody, words, and some aspects of sound. Beat and tempo provide a

rhythmic feel of the piece. The rhythmic feel can be subdivided in

different ways depending on which beat is being emphasised. Time

signatures can be fairly used to represent the rhythmic feel.

So you have local auditive events like a hit of a kick drum, a pitch

for a melody, etc. in music which is then organised into a coherent

abstract structure by our brains using bidirectional processing. Local

events are grouped and organised according to Gestalt principles into

higher level structures and then a top down processing using existing

mental schema and learned patterns affect how we perceive music and

what feelings and emotions it generates within our minds. These two

layers aren't separate, they interact constantly. Our brain uses

previous learned structures to predict the local events while the

local events either confirm or violate those structural expectations.

Syncopation is a primary example of how those expectations are

violated. this constant interplay creates tension and release in the

music.

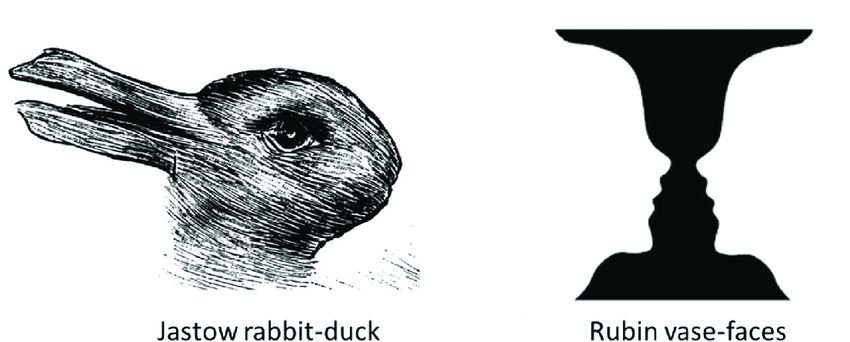

A special case of creating such tension is polyrhythms. Polyrhythm

challenges listener's sense of the meter in the piece of music.

Polyrhythms create a bistable percept which is an important factor in

creating rhythmic tension. Bistable perception is a perceptual

phenomenon in which an observer experiences an ambiguous stimulus in

two different variations. Look at the below image, this is what

bistable percept does to our brains.

Yiu can interpret the objects in the images in two ways. Your

perception is trying to switch its focus from the two variations.

Bistable perception is not just confined to visual stimulus but also

with auditory and olfactory stimuli.

Polyrhythm is an example of auditory bistable percept. The audio

example for polyrhythm has two rhythms, first rhythm is the base 4/4

where you hear the 4 kicks and the other rhythm is the 3 hits of the

clave. The base meter here is of 4/4 which has a counter rhythm of 3/4

on top of it creating tension and gives you a different rhythm

perception with the interaction of the two. In a polyrhythm the

multiple rhythms still share the same base meter or the pulse.

The polyrhythm audio above has a slow tempo and does not feel musical just as a demo so let's listen to an actual track. I recorded this track a couple of days ago where I have added a 4:3 polyrhythm. Let's see if you can recognise the elements interacting as a polyrhythm in the track.

One really interesting phenomenon discovered by researchers about polyrhythms is that trying to keep rhythm during the polyrhythmic tension activates the language areas of the brain called Broadmann Area 47. The hypothesis to explain this phenomena ruses the figure/ground relationship which is also applicable to language. As per cognitive linguistics the figure/ground relationship is fundamental to semantics and cognition in general. The figure represents a concept that needs anchoring and ground represents the concept that does the anchoring. Think of objects in space, for example "the book is on the table" can be semantically understood by the figure/ground relationship. The same principles apply to polyrhythms with your attention between the base and the counter rhythm. When yiu focus on the main meter (figure being the 4 drum kicks) the polyrhythmic meter helps ground the figure whereas when you focus on the polyrhythmic meter (figure being the 3 clave hits) the base meter helps ground the figure. Another brain region called BA40 has been related to directing attention and sustaining in auditory and visual domains. BA40 has also been linked to processing prosodic patterns in human speech and it was found that polyrhythms also activate this region of the brain. Think of prosody (the pattern of stress and intonation in language) involved in conveying irony. Semantically, irony is a linguistic bistable percept, there is a tension between the words and the actual meaning of the sentence. So, naturally BA40 gets activated to process polyrhythms. I guess music and language are not so different at all! Processing music and language activates similar regions of the brain.